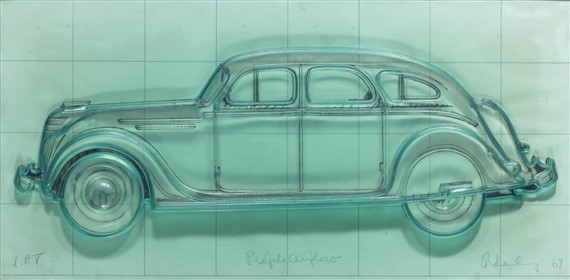

A client called me the other day, looking for a particular print by Claes Oldenburg – “Profile Airflow (Axsom Platsker 59), cast polyurethane relief over lithograph, done in 1969.

So I’m looking around – call me if you have one. But the request got me thinking about Oldenburg, who entered the pantheon of American art with his Pop Art contemporaries some time ago. Where do we put him now?

Pop Art arose as an antidote to the ponderous theorizing of late Abstract Expressionism, a once-adventurous style that had hardened into a technique surrounded by a lot of pronouncements that had degenerated into buzzwords – action painting, the canvas as arena, abstraction as the apotheosis of high art, and so on. Pop Art cheerfully erased the boundary between high and low, between “real” art and “commercial” art — it was often hard to tell whether the artist was presenting an image of, say, a soup can with ironic intent or whether he genuinely admired the product and its packaging.

Coupled with any knowing look was often a sort of goofy happiness, and Oldenburg’s work was the epitome of this. When he made papier-mâché replicas of items of clothing such as the life-sized little girl’s dress below, any critique of Western consumer culture is completely subverted by a sense of fun and the same sort of pride that a third grader might evince in making a similar project.

A similar sense of fun pervades Oldenburg’s large outdoor commissions in which everyday objects are simplified to their essential forms and then expanded to gargantuan size, rendering them simultaneously familiar and strange. Most of us have played badminton at least once, and encountering the shuttlecocks that grace the lawn of the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City for the first time evokes both a start and a smile.

Today, among Oldenburg’s contemporaries in the Pop Art movement, Andy Warhol reigns supreme in influence. Roy Lichtenstein’s reputation, at least as reflected in the art market, is very strong. Tom Wesselman and James Rosenquist seem to be holding steady, at least for signature works from the Sixties. Jim Dine’s reputation has sunk dramatically since his wonder years. And Oldenburg? If I had to prognosticate, I’d guess that the early papier-mâché works will gradually become artifacts of a particular time in art history, more respected than loved (though that’s not to say that they don’t currently command some serious heft among contemporary collectors – the dress depicted above sold at auction nine years ago for $1,721,000). But the elegance of the enlarged everyday objects gives them a classic charm, one that remains even when the objects are no longer used at all (how many people under the age of 40 have ever seen a real typewriter eraser or know how it was employed?).

Even a homely clothespin, when rendered in Cor-Ten steel 45 feet tall, mutates into urbane abstraction, its shape reminding us of what a miraculous thing vision is. That’s an unmistakable sign of real art.

I’ll end with a plug for an organization. I’m on the advisory board for the event “Art Uncorked,” a benefit auction for the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, a wonderful little museum located at the State University of New York at New Paltz. The event is the museum’s major fund-raising event each year, and you don’t have to attend to bid. Two things in particular might interest art-lovers in the New York. The first is a private tour for you and your guests of the American of both the ceramics collections of the American Wing and the Great Hall Balcony of Asian Ceramics at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, led by members of the museum’s curatorial staff. The second is a private tour of the New-York Historical Society, led by Linda Ferber, Executive Director Emerita. The Society’s holdings in Tiffany lamps is world-famous, their permanent collection of art has masterpieces galore, and Linda, as I can attest from personal experience, is a delightful speaker. You can check these and other offerings out at newpaltz.edu/museum/artuncorked.