Earlier this month, I gave a lecture entitled “Appraising the Art of the American West” to a group from the Appraisers Association of America. I spoke about how to set valuations on artworks depicting the American West and its inhabitants by artists from the early 19th century until the present day, and I explained the various factors that make, say, one painting by Frederic Remington more valuable than another of equal size.

One of the artists I discussed in my talk was Charles Bird King (1785-1862). Born in Newport, Rhode Island, King came to New York at the age of 15 to apprentice himself to Edward Savage, a now all-but-forgotten portrait painter. In 1806 King left for London to study with Benjamin West, a famous American painter who had settled there. Returning to America in 1812, King spent the next few years in various mid-Atlantic cities, making a living by painting portraits of politicians and other notables. By 1816, he was living in Washington, DC.

King would be nothing but a footnote in American art history today had he not received a commission from the government in 1821 to paint the members of Native American delegations who were visiting Washington. For the next 20 years, he would paint portraits of tribal leaders as they arrived in town to be shafted yet again by the Great White Father. Those portraits aroused much interest when they were exhibited and later served as the basis for illustrated volumes which are still widely sought after by bibliophiles.

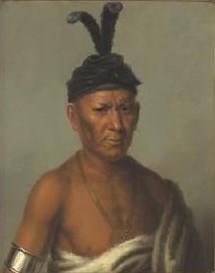

In my talk, I emphasized that what often makes one of King’s portraits more popular, and hence more valuable, is the amount of Native American bling that the sitter is wearing. You want striking face paint, I told them, you want beaded buckskin shirts, bear claw necklaces, eagle feathers, silver medallions. The more bling, the more a King portrait is worth. The painting below, Ottoe Half Chief, hits most of the marks, which is why it sold for $1,352,000 at auction in 2004.

By contrast the portrait Wai-Kee-Chai, Sanky Chief does not have nearly as much finery, which is why it sold for forty percent less, $792,000, in the same sale.

So my motto for appraisers was “With King, you want bling!” Neither of the portraits, however, had the item we most often associate with Native Americans, the eagle feather, which brings me to the second half of my appraisal lesson for today.

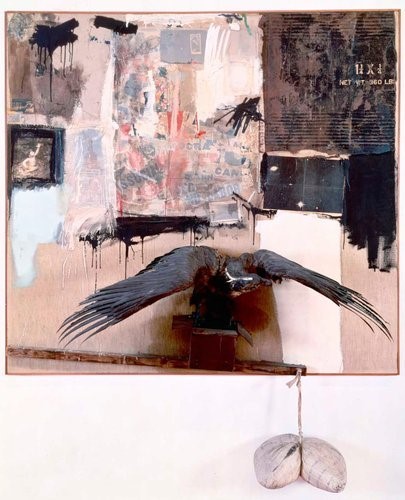

Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) arrived on the New York scene as an enfant terrible in the 1950’s and became famous for the mostly-painting-with-large-collage artworks he labeled “combines.” One of the most famous of these is Canyon, done in 1959. Rauschenberg’s everything-including-the-kitchen-sink aesthetic is evident in the work, shown below.

The artwork includes a dangling pillow, a flattened metal container, a photograph of the artist’s son, and, important for my purpose here, a stuffed bald eagle that one of the artist’s friends had found in the trash and given to him.

The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, passed by Congress in 1940, prohibits the possession or sale of any part of an eagle, alive or dead. When Rauschenberg used the eagle in his artwork, therefore, he was committing an illegal act, despite the fact that the eagle had been dead for at least a half century before he acquired it. Nobody paid much attention at the time, and the work of art ended up in the collection of Ileana Sonnabend, one of Rauschenberg’s dealers. Sonnabend died in 2007, and here is where Canyon enters the domain of appraiser history.

The appraiser for Sonnabend’s heirs gave the painting no value. After all, the appraiser reasoned, the eagle was an integral part of the work and could not be separated from it. Since the sale of a stuffed eagle is illegal, the artwork could not be sold, and if you can’t sell something, how can it have a monetary value? Not so, responded the IRS, Rauschenberg is a major American artist, and this is one of his most important works. They argued that the artwork was worth $65 million, and they wanted $29 million in taxes.

A settlement was eventually reached. The heirs would donate the artwork to the Museum of Modern Art, which would obtain a one-time exception to the law from the Fish and Wildlife Service. There would be no taxes due, but the heirs could not claim any monetary deduction on their taxes.

Thus did Canyon become one of the most striking works in MOMA’s collection. While I can’t sell you any eagles, I won’t sell or lead you to buy any turkeys, either. Seemingly small details can make a big difference in an artwork’s value. I can advise you about such things. Let’s talk.