Thirty-five years ago, I was working for a New York gallery that ran frequent ads in national publications. Our high profile meant that we received inquiries seeking advice about art. One day I received a call from a man who had recently returned from a vacation in Hawaii. There had been an art gallery just off the lobby of the hotel where he had stayed, and the dealer had attempted to interest him in a really good deal.

My caller wasn’t sure exactly what the medium of the work was – he felt sure it was a print of some kind – and he couldn’t remember the name of the artist, but he was struck by the facts that the artist was both famous and elderly and could reasonably be expected to die soon. The dealer had assured my caller that the death of the artist would immediately cause the artist’s prices to rise, and he was wondering whether he should follow up on this marvelous investment opportunity.

“Let me guess,” I asked him, “Was the artist’s name Salvador Dali?”

“Yeah, yeah, that’s right!” he responded. “Dali!”

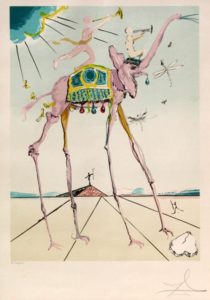

Salvador Dali (born 1904, he would die in 1989) had once been a Surrealist painter of some significance, but by the time of the call, he had long been a caricature of himself, indulging in publicity stunts, appearing on late-night television, and endorsing a variety of products. He was not in good health and was dependent on caretakers who controlled him. It was rumored that he had signed thousands of sheets of blank lithographic paper at their behest, paper that would be used for prints that Dali had nothing to do with.

I told the caller that I wouldn’t touch a late Dali print with a ten-foot pole, particularly not one that was being marketed as that one was. I don’t know what he ended up doing, but these days you can buy all the late Dali prints you want on eBay, with prices starting at a couple of hundred dollars.

My caller was in the grip of an illusion that is the art world’s version of what Wall Street calls the Dead Cat Bounce, a small and brief recovery in the price of a declining stock. The term is derived from the old saying, “Even a dead cat will bounce if you drop it from high enough.” In the stock market, when a stock has fallen to a fraction of its highest price, some brokers argue that the stock is ripe for recovery and that now is the time to buy while the price is low. If enough people believe this and buy the stock, the price will rise. Usually, however, the problems that caused the initial fall reassert themselves, and the recovery proves short-lived.

In the art market, when an artist is elderly, particularly if he has been well-known but is no longer in fashion, some people believe that his prices will rise after his death. The reasoning is that, since the artist’s death will put an end to his art (except perhaps in the case of Dali) and there will be no more new art produced, collectors will be chasing a decreasing number of available works. A scarcity of product will thus cause a rise in price. It’s basic economics.

This belief can lead to rather ghoulish behavior. In the fall of 1989, I was talking with another dealer. “What are you looking for these days?” I asked him.

“Keith Haring,” he replied. “I can sell anything I can get my hands on.” Haring, then 31, had come to notice a decade earlier as a graffiti artist and was now a prominent member of the Lower East Side art scene.

“Is it true that Haring has AIDS?” I asked.

I could almost hear the dealer roll his eyes. “Why do you think his prices have tripled over the summer?” He didn’t add “Duh!” but he might as well have.

“Geez,” I thought. “If scientists came up with a cure for AIDS right now, some dealer would shoot Haring just to protect the value of his investment.”

Despite popular belief, however, the death of an artist does not automatically result in a bull market for that artist’s work, and any sudden rise is likely to be a Dead Cat Bounce. Leave such market gyrations to the art market’s equivalent of day traders. Instead, buy the best pieces you can afford of art that speaks to you. Your guaranteed return on investment will be the years of pleasure that the art gives you. I can help you as you focus on the art you desire. Let’s talk soon.