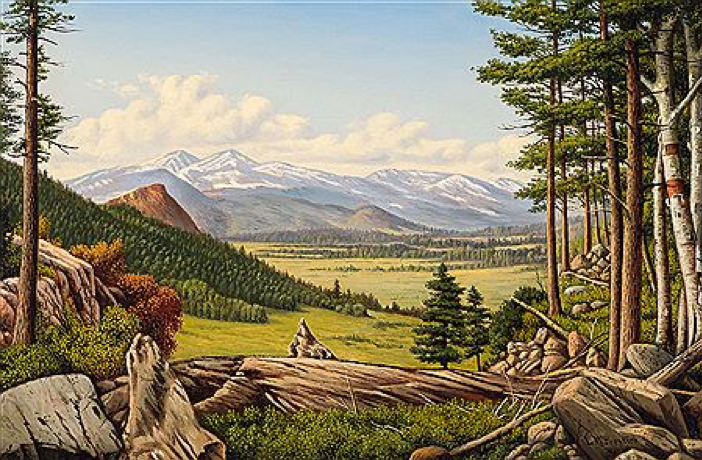

In the course of my day, I often speak with collectors who assembled their collections 30 or 40 years ago and ask them if they might consider selling something. Much of the time, they are still enjoying the lovely things on their walls and have no need to sell. Sometimes, however, they are moving to a smaller home or require funds to cover medical expenses, and they tell me that they want to sell a piece or two. Then we start a process. I send them recent auction records for the artist whose work they might sell, we discuss the current market, and I give them my ideas on how much they can reasonably expect to realize from a sale. It is all very straightforward, but here is where expectations and hopes can collide with reality. The case of the market for the paintings of Levi Wells Prentice (1851-1935) is instructive in this regard. Prentice was born and grew up in Lewis County, New York. He seems to have been self-taught, and we first find mention of him as a painter of landscapes around Syracuse. Though he began as a landscape painter, however, he really thought like a painter of still lifes. Nature in his paintings seems eerily frozen, as Prentice lavishes attention on each leaf, fallen branch, or bit of moss.

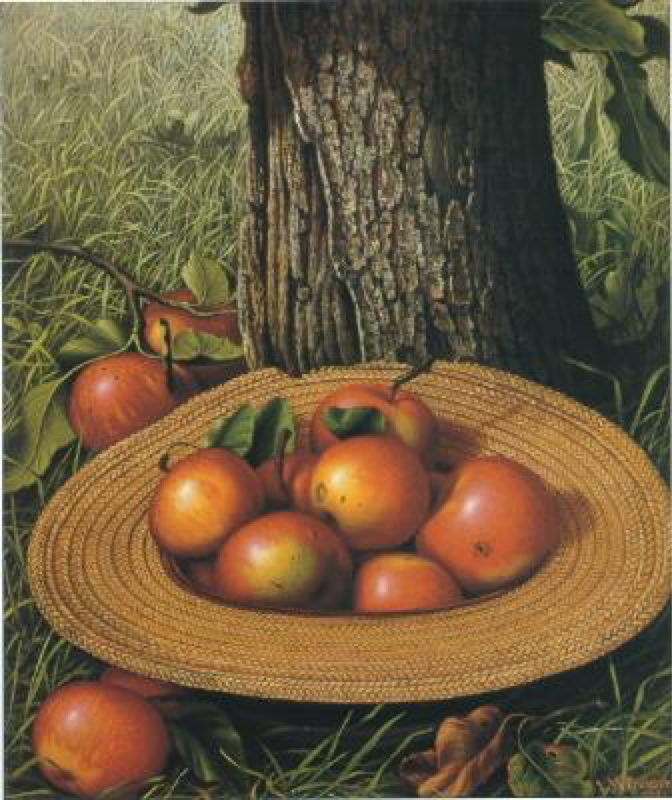

In 1883 Prentice moved to Brooklyn and came into his own. Cut off from the vistas of upstate New York, he began to concentrate on still life paintings of fruit, especially apples, and became a master of the subject. He was only moderately successful in his lifetime, but recognition has steadily grown in the past 40 years, as art historians began to get a full sense of his career. A Prentice painting of apples in a metal bucket graces the cover of William Gerdts’s Painters of the Humble Truth, published in 1981 and still the standard reference on American still life painting of the 19th century, and the Adirondack Museum mounted a major exhibition of Prentice’s work in 1993. Prentice’s rising market reflected the rise in critical interest in the final two decades of the last century. His still life paintings were the works that brought big money. The record at auction was achieved by Straw Hat with Apples, a 16 x 12-inch oil that sold for $134,500 at Sotheby’s New York in 1998.

At the same sale, another Prentice painting of apples sold for $101,500. But those two sales were the high-water mark for Prentice; none of his paintings have cracked the six-figure level at auction since. Indeed, his market has gone steadily downward. Of the thirteen paintings by him that have sold for more than $50,000, twelve of them were sold more than ten years ago.

This is not to denigrate the quality of Prentice’s work. They were wonderful paintings then, and they still are. It is simply that popular tastes have changed. Most of the people who bought still lifes by Prentice and other 19th century artists thirty years ago are now well past retirement age, and few of them are still collecting. The top collectors of today, the middle-aged ones with the discretionary funds to make major purchases, are generally interested in contemporary art.

So what would happen if the current owners of the still life above (I don’t know who owns it) contacted me, wanting to sell the painting? I would tell them that the painting is wonderful, a truly museum-quality picture. But I would also have to tell them that the market is no longer what it was. What could I ask for the painting today — $75,000? Maybe, but $65,000 would be much more realistic, and I’d warn the owners to be prepared to dicker even then.

If they haven’t kept track of the market, and hearing that their painting is now worth about half of what it once was, the owners would probably go through a version of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief: “How can this be?” “I should never have listened to that advisor!” “Can’t we show the auction result to the new buyer?” “(Sigh) No one should buy art.” I’ll leave the fifth stage open, since I don’t know whether the owners would decide to sell and take a loss or whether they would hold on to the work, hoping that the popular taste for Victorian-era still life paintings will come back in their lifetimes.

Most people who spend five figures or more on a work of art make at least implicit assumptions about the equity in the work, but there are no guarantees. If you buy a work of art because you really like it, however, it will reward you with years of pleasure, whether the market for the artist goes up or down due to changes in fashion. When you buy stock, the company’s success may continue, and the stock price may go up. But there are companies that fall on hard times, even if they were once titans in their fields (Eastman Kodak, anyone?). No one can accurately predict long-range trends, either in a particular stock or for a particular artist. When a company fails completely, you lose the value of your investment. In these days of electronic trading, you don’t even have a fancy engraved share to keep. But a good painting will always bring pleasure. Do your homework and then buy the art you love. In terms of personal reward, it will always be a winning investment.