I got the kind of call last month that no dealer, appraiser, or art lover in general ever wants to get. A client called me to say that his home had been destroyed by a fire. He had managed to rescue some of his collection, but most of it had burned completely or had been damaged. He was going to need my services as an appraiser once things had been sorted out.

For the works that had been totally destroyed, the process would be fairly simple. He had an up-to-date insurance appraisal for his collection. If his destroyed Cassatt, say, had been appraised at $200,000, then his insurance company would pay him that amount less any deductible. But what about those cases where the painting had been only partially damaged? That is where he needed me to conduct a damage appraisal.

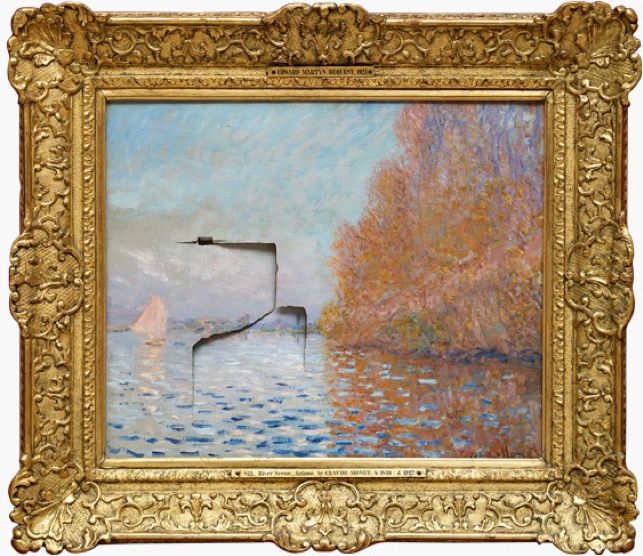

A trained conservator can repair tears and other damage so that it will be invisible to the naked eye. For the Monet shown below (this is not one of my client’s paintings), the edges of the ripped canvas could be joined by a lining on the back of the painting and the “scar” concealed by careful inpainting.

Assuming there was no previous damage to the painting, the repaired painting will still have 99 percent of its original paint, and the condition could fairly be described as “good,” which is defined as “unrestored with no apparent damage to the original condition or restored/conserved/stabilized with concern for preserving the integrity of the work.” The painting, after careful conservation, will look just fine to any casual viewer.

The repaired tears, however, will be apparent in any examination of the painting under ultraviolet light, and the damage will become part of the painting’s condition report in the future. If the painting is offered for sale at a reputable auction house, potential buyers will have to be shown the condition report and be made aware of the damage to the painting. How much lower will the auction house set its estimates for the painting in its current condition than it would have if the work had never been damaged?

Like much of appraising, determining the lessened value of a damaged painting is an art, not a science. Some basic assumptions are fairly obvious. If there’s a tear in a portrait, for example, it matters very much where the tear occurred. If the subject is posed before a dark background and there’s a six-inch L-shaped tear to the background, the tear, once repaired, will have very little impact on the painting’s value. If the tear runs across the face of the sitter, on the other hand, the painting’s value will be significantly affected. The most important part of the painting has been damaged.

There are the scientific facts concerning the damage, and then there is an appraiser’s assessment of the value lost – call it “gut feeling” if you will, but it’s a gut feeling gained through years of experience with works of art, collectors’ tastes, sales records, and the things that make one painting more desirable (and, hence, more expensive) than another work by the same artist. The process may be partly subjective, but there’s a rationale behind it.

I’ll be using my experience to determine how much my client’s surviving paintings have lost in value and, therefore, how much his insurance company has to reimburse him for the loss. Like a lawyer arguing a case, I’ll have to lay out my reasoning in a manner that makes the “jury” (in this case, the insurance company) render a just verdict. I hope that you never require a damage appraisal, Gentle Reader, but if the day ever comes, I’ll be ready to help you.