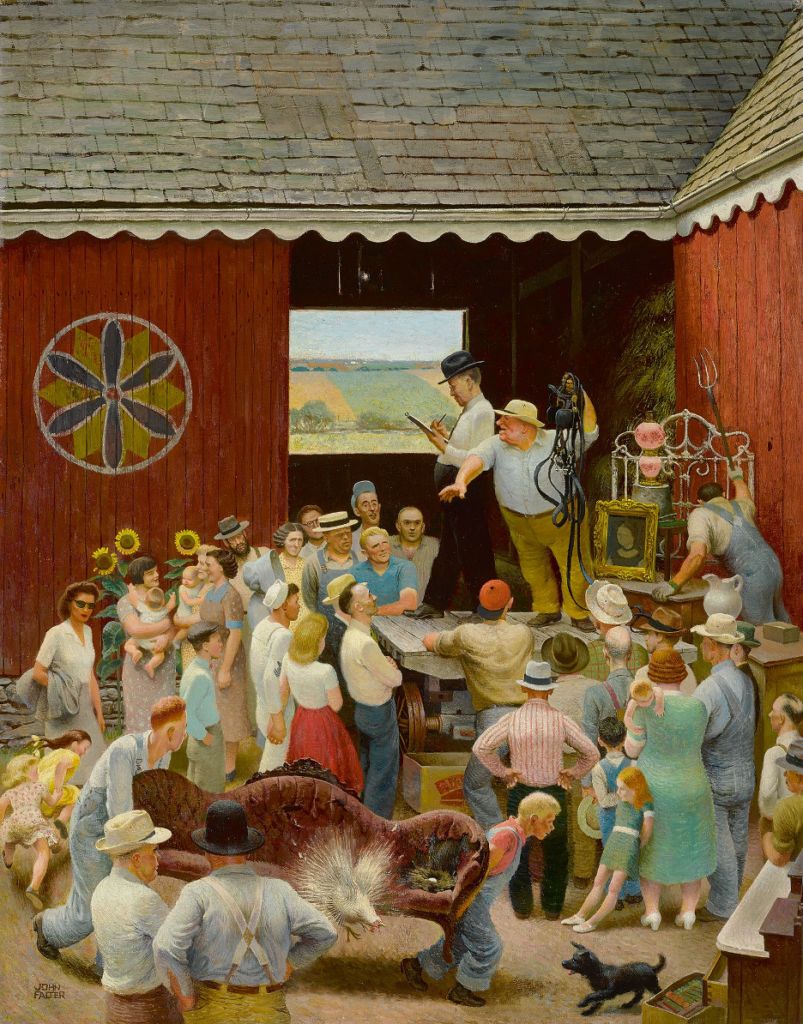

There’s a pleasant fantasy, held even by those who should know better, that goes something like this: You’re on a day trip in the country, and you happen across a little auction being held in a tent in a quaint village. A small painting that attracts you is being offered, and you purchase it for a nominal sum. A few years later, Antiques Roadshow comes to your city, and on impulse you take your painting for examination by their expert. She takes one look at your painting, gasps in disbelief, and stammers, “Why, it’s a long-lost masterpiece by Michelangelo! You’re rich beyond your wildest dreams!”

I call this a fantasy because it ain’t gonna happen. In the first place, the attics of begone days are largely empty, and in the second place, any venue, including a tag sale, will be quickly scanned by “pickers,” people who closely follow such things and who know what they’re looking at. Your chances of finding a lost masterpiece are approximately those of finding a real 5-carat diamond on the tray of costume jewelry at a rummage sale. You’ll be far better off working with a dealer you trust and paying a fair price for a good painting.

Nevertheless, people continue to dream. I once knew a collector I’ll call Bill. I say he was a collector because I think he had once or twice plunked money down for a painting, but he was forever worrying about paying too much for a work of art. Several times, when I showed him a painting, Bill would tell me that he’d had the opportunity to buy a work by that same artist ten years ago for a fraction of my price but that he’d passed on the deal because he thought the price was too high. “I should have bought it then,” he’d lament. I would resist the temptation to grab him by the shoulders, give him a vigorous shaking, and shout, “And twenty years from now, you’ll be complaining that you should have bought this painting today at this price! Bill! Wake up!”

I came to the conclusion that Bill was just a tire-kicker. He was welcome to visit the gallery, but I wasn’t going to waste my time calling him about a work of art I had just acquired. Once, however, he showed up at the gallery in a mysterious mood. He wouldn’t talk to me out front; we had to go into the back room where we wouldn’t be overheard.

Bill had something under his coat, and he pulled it out. “Look at this!” he told me excitedly. It was a copy of Antiques and the Arts Weekly, commonly called “the Bee,” an excellent publication to the trade. The Bee carried then, as it does now, notices of upcoming auctions at small country venues. In the days before the internet, reading the Bee was essential if you wanted to know what was going on. Bill had just discovered it.

“Yeah, Bill,” I told him, “It’s the Bee. So what?”

Leafing through its pages, he said, “Look at this!” and showed me an ad for an upcoming auction in a small town in Upstate New York at a venue that was one rung above a garage sale. The announcement said that the sale would include important works by O’Keeffe, Marin, Hartley, Dove, and a whole Who’s Who of American modernists. There were no photographs of the paintings.

“First, Bill, the Bee has thousands of subscribers,” I said, “so this is not a secret known only to you and me. The real question, though, is what would a collection of important works like these be doing in Frostbite Falls, New York?”

“I called them,” he told me. “It’s an estate sale.”

“An estate sale?” I replied, disbelievingly. “Bill, estate lawyers aren’t stupid. Don’t you think they’d at least call Sotheby’s or Christie’s and ask if those auction houses had ever heard of Georgia O’Keeffe?”

“Oh, no,” he assured me. “It’s just a little town. They don’t know anything.” He wanted to hire me to drive several hours to Frostbite Falls and bid on this trove he was sure he’d found. I refused the offered job, telling him that I was sure the paintings weren’t right. “Don’t waste your time on this,” I advised.

He left, disappointed, but the next time we saw each other, he confessed to me that he hadn’t let the matter go. He had chartered a small plane and flown up to the town to cash in on this coup. Upon seeing the paintings, he was dismayed to see that the paintings were obvious fakes. “I was so mad,” he told me, “I asked them, ‘How could you say this is a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe?’ and they said, ‘Well, it’s signed Georgia O’Keeffe’.”

I have lost contact with Bill since that time, but if he’s currently above ground, I don’t doubt that he’s still trying to put one over on the hayseeds of Pumpkin Junction. In these days, when even small auction houses have websites with photos and when dealers and collectors can put out a notification alert to inform them of works by an artist they like coming up in venues from coast to coast, your chances of stealing a work at a small auction are about those of hitting the jackpot in the state lottery. Buy the lottery ticket and save yourself a lot of gas.