There are two kinds of collectors that can make a dealer tear his hair. The first kind don’t know exactly what they want; they’re just in the mood to buy something. “I’ll know it when I see it,” they tell you. You end up pulling out paintings of every conceivable style and subject, but none of them seems to fit the potential clients’ ideas of what they want to see hanging on their walls.

The second kind know exactly what they want and won’t consider anything else. It may be a particular color scheme – they want something mostly purple for over the sofa. It may be a particular subject — a King Charles Spaniel, a view of Venice, or a still life of raspberries. Raspberries and Venice are fairly easy to come up with; King Charles Spaniels, less so. Unlike me, who can tell a bulldog from a chihuahua but not much more, dog fanciers know precisely what their favorite breed looks like and are quick to tell you that what you’re offering as a painting of an English Setter is actually a Llewellin Setter, and you ought to be ashamed of your ignorance. Small wonder that there are art dealers specializing only in dogs.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting a particular color or subject when you’re looking to buy art. As I tell collectors, it’s your home. You have every right to buy something that will give you nothing but pleasure when you see it hanging on your wall. If a particular dominant tone in a painting will catch the light in your room just right and will make the room one in which you love spending time, go for it.

Though I said above that collectors who want something particular can make a dealer tear his hair, they’re also fairly easy to deal with. Either I have what they want or I don’t, so there’s not a lot of time wasted. I assume that the collector is going to send his query to other dealers in the field, so I don’t bother calling them. If I know of something in a private collection that might fill the bill, I’ll give the owner a call and see if he or she might possibly sell. Otherwise, I simply tell the seeker “sorry,” and make a note in case something turns up one day.

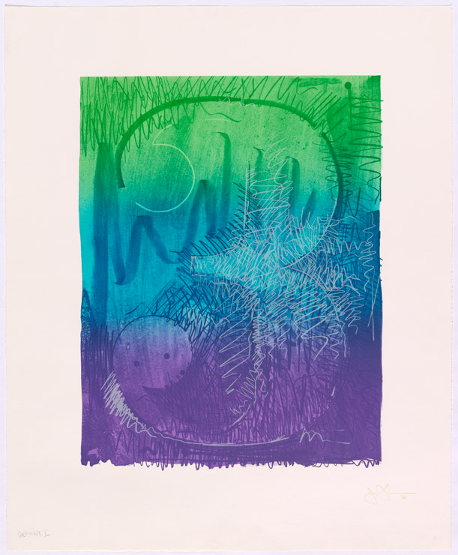

I am currently working with a collector who falls into category two. He wants an image of Number Three by Jasper Johns.

“Why Number Three?” I queried him. He replied, “With our kids, we have always waved 3 goodbyes and signed our letters 3. It represents, ‘I love you.’ Occasionally folks see us doing this and comment that they do, too. We also have three kids and the only two with kids have three kids each, so we think the number belongs totally to us. We just don’t own it.”

Anybody have one? If you do, give me a call and let me know what you want for it. It’s time to spread the love.

********

By the way, unless your social distancing has also been news-free for the past 30 days, you’ve probably heard that the Non-Fungible Token (NFT) artwork by Beeple that I mentioned last month ended up selling for $69,000,000, making it the third highest-selling work by a living artist. It was bought by the owners of a Singapore-based NFT production studio and crypto fund call Metapurse. While Metapurse has been around since 2016, its owners have only recently begun to invest in artwork.

While Christie’s, the auction house that held the sale, originally wanted to be paid at least in part in traditional currency, they eventually agreed to accept the entire payment in Ethereum, another cryptocurrency platform. That means, of course, that Christie’s can currently access the funds only in this very limited digital platform. They can pay their consignor, Beeple (a.k.a. Mike Winkelmann), out of that purse, but as far as I know, they can’t use digital currency to pay their employees’ salaries or pay the utility bill.

I know that I’m a dinosaur, and I know that there are many financial instruments we take for granted today that would once have seemed outlandish. 150 years ago, employees got paid in greenbacks. Then came paychecks. Even 50 years ago, the idea of direct deposit of salary or Social Security benefits to one’s checking account would have seemed like something out of The Jetsons.

But until you can take bitcoin or one of the other cryptocurrencies to the supermarket and use them to buy groceries, it’s still funny money. I am reminded of the joke about a man who offered his dog for sale at a price of $1,000,000. One day, the dog was gone, and when people asked the man if he had sold his dog, he said no, he had swapped him for two $500,000 cats.

We’re moving toward a cashless society, one where the thing we call money is increasingly a digital matter, transacted in a binary code of ones and zeros. Art may eventually become a matter of such numbers, but I’m betting that, in my lifetime at least, there will still be a hunger for ineluctably physical artworks. Like Jasper Johns’ Number 3. Give me a call if you’ve got one.