I like to say that there was only one truly creative genius in the whole of art history: the first caveman (or woman) to draw a mastodon on that cavern wall. All other artists have been stealing from him or her ever since.

I’ve been reminded of this assertion lately while working on a series of lectures on American art that I’m giving for the Lifetime Learning Institute at Vassar College. Reviewing the biographies of the noted artists of the Colonial Era and the first years afterwards, I was struck time and again at how difficult it was for a would-be artist to learn his craft back then.

Art needs other art, unless you’re the prehistoric genius mentioned above. Books were expensive and difficult to come by, but a budding poet in Colonial America had a chance to learn his craft from the works of Shakespeare or Milton. At the very least, he could undoubtedly lay hands upon one of the masterpieces of English prosody: the King James Bible.

But what could painters see? The masterpieces were in Europe. If you were in Boston, you came up against the Puritans’ suspicion of visual art, a consequence of the Second Commandment’s prohibition of graven images. If you were in Philadelphia, you had to battle the Quaker aversion to anything that was not deemed plain and modest. There were no magnificent church altarpieces or frescoes to encounter at Sunday worship, no princes displaying works in their palaces. John Singleton Copley, writing as a young artist in 1766, complained in a letter to Benjamin West, who was working in England, “In this Country as You rightly observe there is no examples of Art, except what is to [be] met with in a few prints indifferently exicuted, from which it is not possable to learn much.” (Copley’s art was already much better than his spelling.)

There were few visiting artists from England to encounter in the colonies. The well-recognized ones stayed home, where the big money was. At most a second-stringer might visit America for two or three years to try and fatten his purse by painting wealthy merchants and their wives. It is little wonder that many of the first American artists to achieve note fell under the description “Clever young lad, good with his hands.” Apprenticed to saddle makers, metalsmiths, clock makers, and house painters, these young men snatched art instruction where they could.

Benjamin West, the first American to achieve widespread fame as a painter, was the tenth child of a tavern owner. Still in his teens, he met John Wollaston, an English painter who was making the rounds from Boston to Virginia, painting portraits. Wollaston’s advice made West a better painter, but the young man would have remained an eternal provincial but for the luck of a commission from a literary-minded gunsmith, who engaged West to paint The Death of Socrates after an engraving in a book on ancient history. The resulting painting was seen by the provost of the College of Philadelphia. Impressed by the young man’s promise, the provost enlisted William Allen, reputed to be the wealthiest man in Philadelphia, to sponsor West for a European tour lasting three years, during which the young artist absorbed the lessons of France and Italy.

Buoyed by his experiences in those countries, West stopped in London in 1763 for a visit before his intended return to America, but he never left. He met prominent artists and writers there; just as important, he met Church of England bishops who commissioned works from him. His painting, The Death of General Wolfe, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1771, was widely reproduced and made his name.

A year afterwards, King George III appointed him historical painter to the court. West would later head the Royal Academy and serve as a teacher to several American artists who came to England to study.

For an aspiring artist from America, then, it was hard to get to Europe and sometimes harder still to go home. Why give up the chance to win fame as a painter of grand religious or historical scenes to go back to America instead for a career of painting stolid businessmen and their families? Yet some did. Charles Willson Peale spent three years in London, studying with West. Unlike West, who stayed in London and kept any sympathy for the American independence movement unmentioned, Peale returned to Philadelphia, where his service in the Pennsylvania militia during the Revolutionary War stood him in good stead when he sought to paint such noted figures as Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and John Hancock.

The real cash cow for Peale, however, was George Washington, whom Peale had met before the war. From seven sittings with the great man, Peale would eventually produce almost 60 portraits. (He did not sell the portraits done from life, keeping them instead as models to copy.)

Another American artist who recognized the cash potential in Washington was Gilbert Stuart, who had had to go to England because of his Loyalist sympathies. He remained there throughout the war, studying with West and exhibiting at the Royal Academy. Stuart grew to be in great demand as a London portraitist, but his profligate lifestyle often put him in danger of debtor’s prison. Then, as a biographer has said, “In 1787, he fled to Dublin, Ireland, where he painted and accumulated debt with equal vigor.”

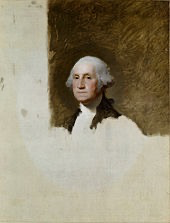

Seeing himself in danger again, Stuart came up with a possible solution. Since the war, Washington had been idolized in America, and there was bound to be a huge demand for portraits of “The Father of His Country.” If he could paint Washington, the sale of engravings based on the painting ought to provide a reliable income. Accordingly, in Stuart left for New York in 1793, where he pursued portrait commissions from influential people who might introduce him to the great man. His scheme worked: John Jay gave Stuart a letter of introduction to Washington, who posed for him in 1795.

Like Peale, Stuart was canny enough not to finish the life portrait he had done, keeping it until his death. It became the model for scores of copies Stuart painted and sold for $100 each. (The original is now jointly owned by the Boston Museum of Fine Art and the National Portrait Gallery.)

Even a cash cow, however, eventually runs out of milk, particularly when it is owned by someone so untidy in financial matters as Stuart was. In 1828 he died in debt in Boston and was buried in Old South Burial Ground in an unmarked grave, his family being unable to afford a headstone. Years later, when his family wanted to move his remains to his hometown of Newport, Rhode Island, no one could remember exactly where the grave was, and Stuart has remained buried in Boston to this day.

Art and Money — two worlds which are inseparably entwined. For colonial artists, the challenge was to come up with the funds to get an art education and then to develop the clientele to provide a livelihood. For the works those painters left behind, survival generally depended upon how much the works were valued in terms of money as well as their makers’ reputations. In my series of talks, “American Art Through an Appraiser’s Eyes,” I’ll be talking about both. If you have a painting you’d like valued, I’ll be happy to do an appraisal. Let’s talk.