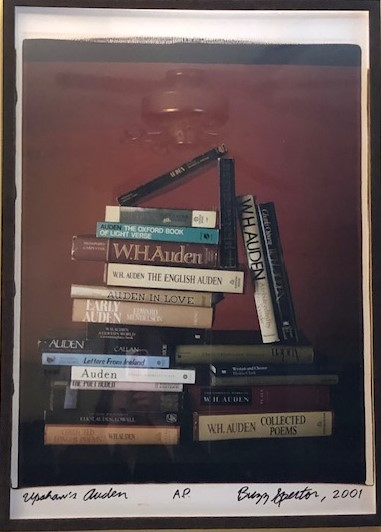

One of the upsides to being friends with artists is that sometimes they give you works of art. One of the downsides to being friends with artists is that those works are often unframed. You’re glad to receive a work, but, if it’s unframed, you can’t hang it, and if you’re don’t have the time or money to get it framed, the work will end up in a closet or under a bed. You’ll subsequently find yourself hesitating to invite your friend for supper, fearing she will notice that the work is not on display. Which she will. Our artist friend Buzz Spector, being a prince of a fellow, has let that cup pass from us by making sure that every work he has given us over the years has come framed. As a result, Roberta and I are curators for what Buzz once described as the country’s largest permanent Buzz Spector exhibition.

Collection Reagan and Roberta Upshaw

Laying aside their function as protection for artwork, frames are important. “A good frame will make a gentleman out of a rascal,” art dealer David Findlay once declared. What constitutes a great frame, though, is a matter of constantly shifting opinion. I knew a frame dealer who got his start 50 years ago at a time when there was a vogue for reframing Hudson River School paintings in small frames that were “less gaudily Victorian.” The dealer acquired some of his early inventory by snatching discarded 19th century frames from trash set out on Park Avenue sidewalks. He sold them for tidy sums years later, when collectors were again demanding period frames for their paintings.

In women’s fashion, there are certain designs that are described as timeless. These designs find popularity again and again, even as their lines are tweaked by modern designers. Other fashions find ridicule as memes on Facebook with captions like, “What on earth were they thinking?”

Frames also have their fashions. There are classic styles, and there are fads. Paintings by Picasso or Botero are often displayed in replicas of 17th century Spanish frames which set the paintings to advantage and call to mind their predecessors in the history of Spanish art. On the other hand, gold strip moldings with burlap liners, popular in the 1950’s, make the paintings they surround look hopelessly outdated today.

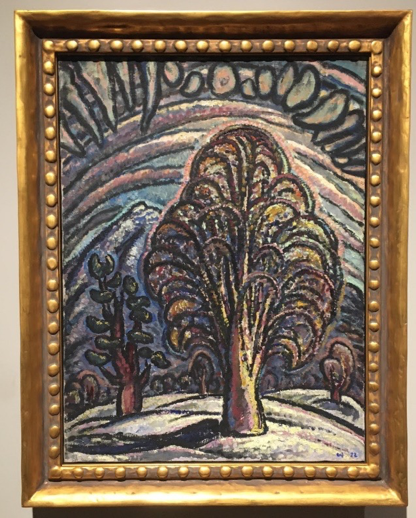

When Roberta and I visit museums, we often spend as much time commenting on the frames as on the paintings, for they’re a package. We recently went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art with our friend Nina Foster, the daughter of artist Harold Weston, to view one of her father’s paintings, a lovely Adirondack landscape. Nina had donated money to the museum to have the painting reframed in a replica of the frames Weston had carved by hand for his paintings when he was preparing for his first New York exhibition in 1922. The new frame made a perfect accompaniment to the painting, though as curator Katharine Foster noted, it raised a bit of a problem in the painting’s relation to works hung nearby that bore modest frames. It’s like your neighbor fixing up his house, Kathy remarked; suddenly yours looks a bit run down.

Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. S. Emlen Stokes 1979-13-1.

Photo courtesy Jessica Smith.

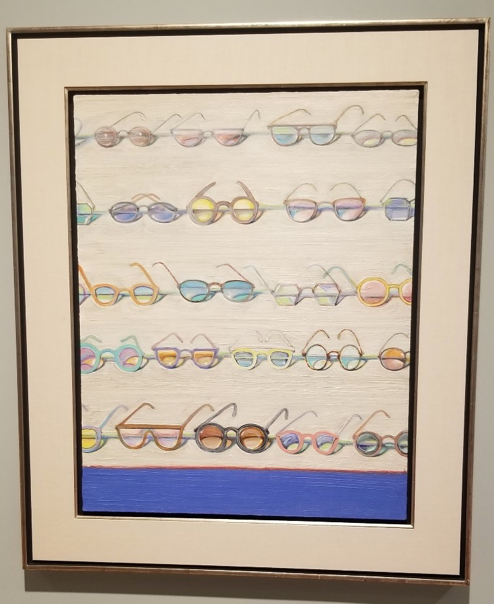

When you’re in a museum, take note of the frames as well as the paintings. What works? What looks inappropriate? Why? We were recently at the Brandywine Museum, enjoying a wonderful exhibition of works by Wayne Thiebaud. I was struck by the decision of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation, which owns many of the works on display, to frame their oils basically as works on paper.

Wayne Thiebaud Foundation.

An oil on linen at least a couple of feet high has been framed as if it were a 10 x 8 inch drawing. Was the linen mat necessary? To me it was distracting. I preferred the oils framed in a more traditional manner.

Collection Crocker Art Museum.

I found Boston Crème’s framing much more effective, strongly supporting the painting rather than distracting from it.

Well, if it’s your collection, you can frame the works as you please. Speaking of my own collection, I’m in the process of buying a frame for a large painting that was given to me a few years back by Vernon Fisher. It was a generous gift, and I have felt a twinge of conscience from time to time over its languishing unframed and unseen. I’m excited at the prospect of having it hanging in our home. Now the question is where. Do I crowd the walls even more, or do I send someone else’s painting to storage? If we opt for the latter, Roberta and I will have to monitor our dinner invitations carefully and be prepared to make a switcheroo at short notice. For the artist will notice his painting’s absence. He always does.