I was manning a booth at an antiques show in Denver many years ago when a man came in, carrying a manila envelope from which he removed a photograph of a painting. “I’ve got a Winslow Homer that I want to sell,” he informed me.

I was always interested in acquiring a Winslow Homer painting, so I examined the photo carefully. “Has Lloyd Goodrich seen the painting?” I inquired. Goodrich, a noted scholar and former head of the Whitney Museum of American Art, was in the process of compiling the catalogue raisonné for Homer’s work.

“LLOYD GOODRICH!” the man said, practically spitting in disgust. He went on a rant against Goodrich, who had declined to include his painting in the catalogue, questioning the scholar’s knowledge and honesty. He began pulling papers out of his envelope. “Here’s a paint analysis! And the canvas dates from Homer’s lifetime!” And on and on. He pursued me across the booth as I backed away.

I finally got rid of the man, explaining that, whatever his beef with Goodrich, I had no standing in the matter. I wasn’t going to sell a work that was not going to be included in the catalogue raisonné. It would have been an invitation for a lawsuit down the line.

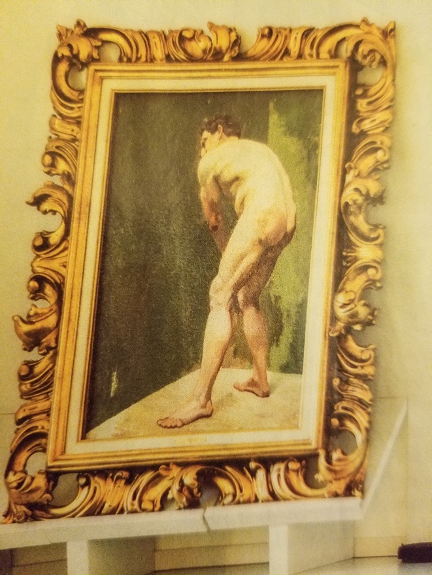

I was reminded of my antiques show visitor by an article by Sam Knight in a recent issue of The New Yorker. “An Uncertain Image” tells the story of a European collector who owns what he believes to be a painting by the British artist Lucien Freud. The collector bought the work in 1997 as “attributed to Lucien Freud” for $70,000, about a third of what a recognized Freud painting would bring at that time, in a sale of unclaimed property near Geneva.

A few years later, the collector put the work up for sale as a Freud painting on eBay, but the listing was cancelled by the site, which said that a complaint had been raised by the 80-year-old artist himself. The collector claims that he received a call from Freud a few days later, saying it wasn’t by him. Next, according to the collector, Freud offered to buy the painting for twice what the collector paid. When the collector refused, Freud angrily told him that he would never be able to sell the painting and hung up.

Freud died in 2011, and the collector is still trying to get his painting acknowledged as genuine. Freud’s estate and noted Freud scholars have declined to accept the painting’s authenticity, but the collector hasn’t given up. He’s hired laboratories to have the paint sampled. He’s had artificial intelligence employed to analyze the painting’s brushstrokes and palette and to compare those results with recognized Freud paintings. He’s tried to get Freud’s fingerprints and match them to a partial print found on the bottom edge of the canvas.

It’s been for naught so far, but as Sam Knight writes, “Some quests never end. [Nicholas] Eastaugh, the pigmentation expert, told me that he sees it a lot: the bulging file, the flights from one European city to another, the latest invoice for a round of bomb-pulse radiocarbon dating.”

Any dealer who’s been in business for many years has met painting owners who swear that the catalogue raisonné committee is wrong and have documents that they think prove it. What’s undeniable is that, as with the purported Freud, the paintings in such cases are generally of low quality, works that would be difficult to sell to anyone who wasn’t simply seeking an autograph. As I like to say, scholars have two categories: real and fake. Dealers have three: real, fake, and who cares? I’ve never seen a questionable painting that I’d have wanted to purchase, even if it could finally be determined to be genuine.

When in doubt, if the artist is still alive, ask him and accept what he says. If he offers you twice what you paid, take the money and run. The most bizarre art world lawsuit I’ve heard of came six years ago when artist Peter Doig, whose works sell at auction for millions of dollars, denied authorship of a painting. The owner of the work, a former corrections officer at the Thunder Bay Correctional Center in Canada, claimed that Doig had painted the work when he was 17 years old and an inmate at the facility. Though Doig remonstrated that he had never been locked up at any institution and pointed out that the signature on the painting was “Doige,” the $5 million lawsuit brought by the owner and a dealer who was going to sell the work once it was authenticated was allowed to proceed. Doig won in the end, though I shudder to think about his legal fees.

In the boilerplate section of the appraisals I write, there’s a standard disclaimer that, while I see no reason not to believe the work is genuine, I am not an authenticator and do not guarantee the authenticity of the work. $5 million lawsuits are the reason why.