Suppose I came into a possession of a box of junk from my childhood that my mother had neglected to throw out. Included in the box might be an old baseball from my Little League days. What would that baseball be worth? Nothing, of course. You couldn’t even play ball with it — it would be so brittle that it would probably not survive a good whack of a bat. But suppose I could convince you that this old baseball was the very ball that Roger Maris hit over the wall for his 61st home run in 1961. What would it be worth then?

Form and color can make an object beautiful, but only a story can imbue an object with magic. It has increasingly become the job of an auctioneer to attach a story to an object. At the annual conference of the Appraisers Association of American three weeks ago, Bruno Vinciguerra, the CEO of Bonhams, declared, “We’re in the business of passion.” If you want to get a record price for an object, said Vinciguerra, you need to present it as part of a compelling story, and you need to persuade a potential purchaser that he or she can be part of that story.

It strikes me that the hunger such a tactic feeds is analogous to the selfie. I recently visited the Diego Rivera exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Twenty years ago, visitors might have been content to view Rivera’s paintings and purchase a postcard or two of their favorite works. Not anymore. The smartphone has done more than allow viewers to take souvenirs: at any exhibition these days, you see people taking selfies with a painting behind them. It’s not just Diego Rivera’s Flower Carrier, it’s ME and Diego Rivera’s Flower Carrier. Such selfies allow you, at least in imagination, to catch onto the coattails of the great.

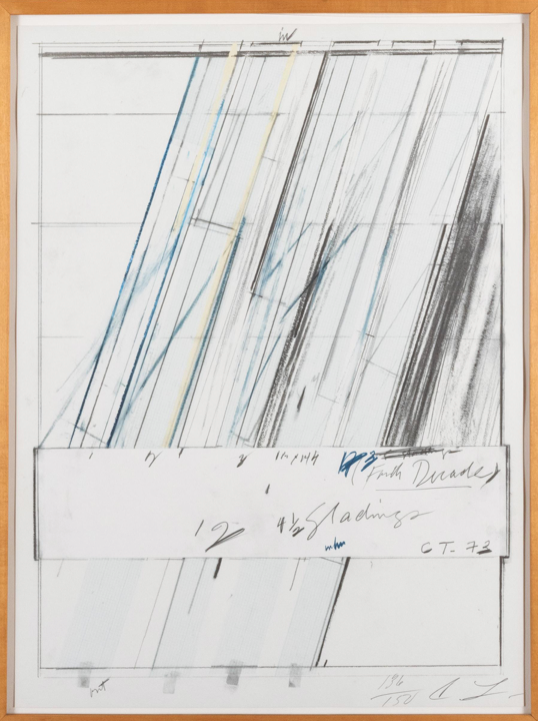

This coattail-catching phenomenon doesn’t occur only with art. Bonhams’ sale of the library and personal property of Ruth Bader Ginsburg this fall brought in a total of $3.1 million, five times its estimate. People wanted to own something previously owned by a woman they admired. It doesn’t even have to be at a New York or London venue for this to happen: a month ago, Stair Galleries in Hudson, NY, garnered eye-popping prices with its auction of the personal effects of writer Joan Didion. A group of desk items, including scissors, a box of pens, and a clipboard, brought $4,250. Didion’s art collection set records: a Cy Twombly lithograph which was estimated at $5,000-7,000 and had never previously sold for more than $8,830 at auction hammered down at $50,000.

Someone evidently felt that looking at the actual print that Joan Didion had seen every day was worth over $40,000 more than the other 149 prints in Twombly’s edition. (As an appraiser, by the way, I have to be extremely careful about including results from celebrity sales in the comparables I gather when determining value. I generally exclude them from the comparable analysis, as they skew the average.)

The premium which accrues to an object because of an illustrious former owner is not a new phenomenon, of course. People have always hungered for a connection to a greater history. Smart auctioneers know how to whet that desire. In a blockbuster sale, said Vinciguerra, the auction house has made use of the three unities of French classical drama – plot, time, and place. A story has been constructed, and it moves with seeming inevitability to a time and place – an object with a compelling story is sold on a particular day at a particular auction house. Their job is to make you feel you must become part of the plot. To insert yourself into that object’s provenance is to become part of the magic.

* * *

I used to say that Impressionism was the last art movement to be genuinely popular with the general public. Is that still true? Certainly, when you visit the Met, the Impressionist rooms are crammed with visitors. But just as “brown furniture” has suffered a sharp decrease in value over the past 30 years, ignored by younger collectors who prefer mid-Century Modern, the pretty pictures of the previous century are not as compelling to buyers as they once were. As with 18th century furniture, an Impressionist masterpiece, something truly singular, can still bring a record price, but average works by second-generation Impressionists don’t bring what they once did. They’re seen as being of your grandfather’s taste, and younger people don’t identify with paintings of ladies with bustles and parasols.

Even members of the original Impressionist group are not immune from this change of taste. Renoir has probably suffered the most from the trend; his record price was achieved over 30 years ago, though a spectacular piece can still bring well into eight figures. One of the original Impressionists, however, has bucked the trend, at least where his late works are concerned: Claude Monet.

At the Appraisers Association meeting, David Norman, former head of the Impressionist and Modernist division at Sotheby’s, discussed this phenomenon. For years, said Norman, Monet’s late paintings of waterlilies, left in his studio at his death, were always a problem to sell. They were large, many of them six feet wide or more; they were unfinished, especially in the corners; and they were often unsigned. The lack of form, compared with Monet’s earlier works, led some critics to wonder whether their comparative looseness was the result of a changing aesthetic or cataracts.

The market has caught up with these works, however, and their looseness does not bother a generation of collectors that has grown up on Mark Rothko or Philip Guston. Monet’s late works can now be seen as precursors to the Abstract Expressionists, and they continue to inspire young artists today. The market reflects this as well. The Waterlily Pond sold for $70,353,000 in May, 2021.

Magic, money, and the madness of art. If you want to talk about any of them, call me.