I ran into Robert Simon at an Appraisers Association reception recently. Bob is one of the preeminent dealers of Old Master art in America, and I took the opportunity to ask him about the current state of the Old Master Market.

I was surprised, though I shouldn’t have been, to learn that Old Master collecting is being shaped by many of the same factors that currently affect the collecting of 19th and 20th century art by museums. I say “museums” because the vast majority of Old Master sales are to museums. Public institutions have been under pressure to expand their collections by acquiring works by women and artists of color, and that pressure has been applied to the field of Old Masters as well.

Works by Artemisia Gentileschi and Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun have sold for over $5 million and $7 million, respectively, in the past five years. Artists of color working in Europe during the 15th-18th centuries are understandably rare — I can’t think of any from the Renaissance and only a handful from the 18th century – but when such works come on the market, there is a bidding war. Paintings from that era by white artists that include persons of color as subjects are also in high demand, but the people depicted have to be shown as individuals, not as “types.”

Dealing Old Master works, however, has challenges unlike dealing in 19th and 20th century art. To state the obvious, most masterpieces long ago passed into the collections of museums, and even if a dealer acquires a major work from the wall of some nobleman’s castle, getting an export permit from the country where the owner lives can be difficult if not impossible. Questions about attribution and condition are particularly problematic. And there’s a new challenge – for the past 30 years, there has been a concentrated effort made to locate works of art stolen from Jewish collectors by the Nazis and to return those works to the collectors’ heirs. A dealer in Old Master art must rigorously review the provenance of works being offered to him, always aware that a lawsuit over title may be waiting to happen.

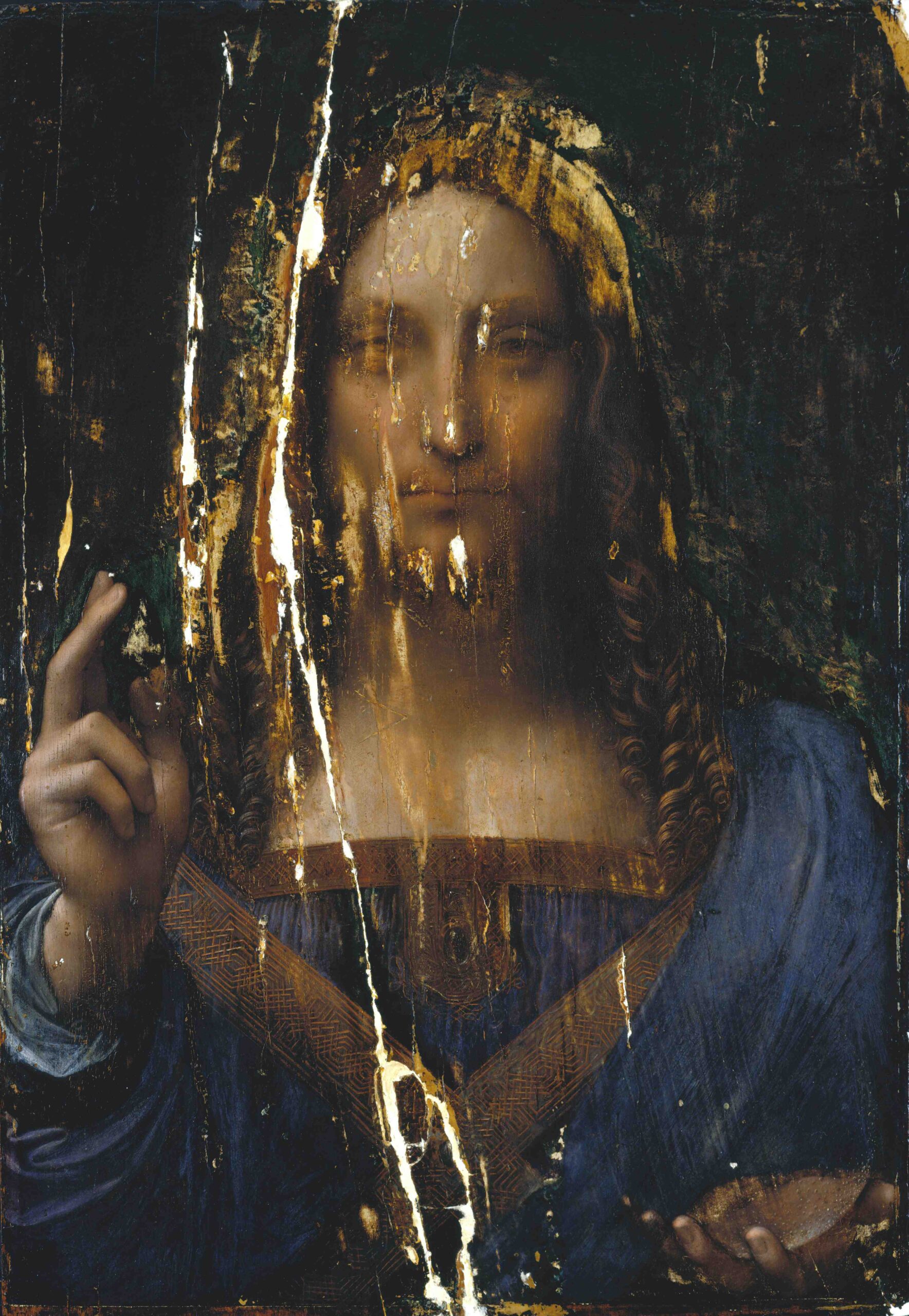

For all its challenges, dealing in Old Masters can be quite lucrative when once-in-a-lifetime discoveries are made. Bob was part of the consortium of dealers who took a chance on a begrimed old portrait of Christ, listed as a copy of the lost Leonardo da Vinci painting Salvador Mundi, that came up for sale at an obscure Louisiana auction house in 2005. The consortium paid $1,175 for the painting. After cleaning and much research, it was announced that the painting was an original work by Leonardo.

Attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi. Photo taken after cleaning and before restoration. Photo courtesy Google News.

In 2013 the consortium sold the work to a Swiss dealer for $75 million. The dealer sold it to a Russian oligarch for $127.5 million. In 2017, the work was consigned to Christie’s, which did a brilliant job of marketing, touting the piece as “the male Mona Lisa” when they showed it at their galleries around the world. At their New York space, Christie’s paired the work with an Andy Warhol painting based on Leonardo’s Last Supper. The line to view the two works was around the block. At the auction, the painting sold for over $450 million. The buyer was later revealed to be Saudi prince Mohammed bin Salman. Far from being jealous, Bob tells me that he takes his hat off to Christie’s for what they were able to do with the piece.

Every dealer dreams about finding something like Salvador Mundi, although the chances are about those of winning the lottery. In my first job in the New York art world, however, I worked for Ira Spanierman, who had had a similar Old Master miracle. I’ll talk about it in some future blog. In the meantime, if you’ve got a painting that shouts “Leonardo!”, give me a call.