Two roads diverged in a yellow wood . . .

~Robert Frost

Last summer I visited the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. It’s a terrific little museum and well worth taking time to visit when you’re in the Boston area. The Addison Gallery had mounted a retrospective exhibition of the work of Alfred Maurer (1868-1932), and I was eager to get a full view of the artist’s achievement. I was going through the exhibition as any art dealer would, i.e., reading the wall label credits and thinking, “Is this painting owned by an institution, or was it loaned by a private collector whom I can call to try and get it for sale?”

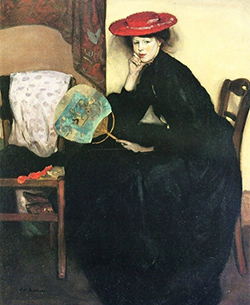

I was particularly taken by Maurer’s work done in Paris during the first years of the 20th century, especially his portraits of women such as Model with a Japanese Fan, painted around 1903.

The influence of Whistler is plainly there, of course, but there’s also something of the bold, new century. The woman is clearly not the languid Dame aux Camélias model beloved by the previous generation. Her gaze confronts the viewer directly, and for all her elegance, there’s something rather earthy in the cluttered interior with objects tossed upon or draped across the chair at the left.

Looking at such paintings, I thought of a Maurer painting I knew in a private collection and made a mental note to call its owner when I got home and see if she might be willing to sell. When I got home and went through my notes, however, I realized I was thinking of a different artist. His painting is below:

Woman Sitting at a Table, done at the same time as the Maurer work already depicted, is actually by Richard Miller (1874-1943), another young American artist who had come to live and study in Paris. Both artists had studied at the Académie Julian and were members of the American Art Association, where expatriate American artists gathered. They undoubtedly knew each other. Miller’s work of this period shows many of the same influences as Maurer’s, particularly that of Whistler.

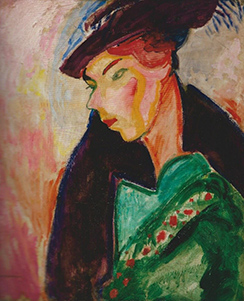

The similarities which made my confusion understandable, however, are fascinating in light of the two painters’ subsequent artistic trajectories. Five years after the paintings above were painted, Maurer had discovered the Fauves and incorporated Matisse’s influence into such pictures as Head of a Woman, below:

Miller moved in the opposite direction, moving (retreating, some critics might say) into a decorative Impressionist style still infused with academic draftsmanship, as in The Milliner, below:

I use the word “retreating” above as an indication of how Maurer and Miller were viewed by the past generation of art historians. Maurer was seen as an artist who boldly followed the modernist imperative and developed into a significant artist, while Miller was dismissed as an academic artist who had lacked the courage or vision to join the avant-garde and was therefore unworthy of a place in Serious Art History.

The collapse of the modernism paradigm, however, has made historians more willing to look at an artist’s work on the artist’s own terms. I had a professor once who warned us budding scholars of the “it becomes” fallacy, that is, “So-and-so’s style becomes more expressionist,” as if style were something separate from the artist, or “So-and-so’s style is proto-baroque,” as if the artist were striving to become a baroque painter but somehow just couldn’t get there.

Maurer and Miller were both talented artists who responded to the world around them in different ways and who solved aesthetic problems on their own terms. They took different roads in pursuit of their visions, and they achieved distinction in their mature styles. For my taste, however, they never painted better than they did as young artists in Paris a little over a century ago, each newly in possession of his powers and each hungry for a world still to win.

P.S. I did call the owner of Miller’s Woman Sitting at a Table, and I have it for sale. Call me.