If you asked a hundred urban twenty-somethings to describe themselves, a fair number would define themselves as artists of one sort or another. “I’m a painter,” a few would tell you. “I’m an actor,” others would say. Jazz saxophonist, dancer, standup comedian – the entire gamut of art forms would probably be found in the self-descriptions of those hundred young people.

A tiny percentage of our hypothetical group will go on to achieve commercial and critical success in their fields. The vast majority will not. Of the also-rans, most will come to their senses sooner or later and take conventional jobs. But there are a few souls who carry their self-definition as artists with them despite their lack of commercial success. If you define yourself as a painter, then you paint, whether or not you can sell your paintings. Samuel Rothbort (1882-1971) was one of these artists.

Rothbort was born in Vawkavysk (Polish: Wolkovisk), a town now part of Belarus. In keeping with Jewish life in the shtetl, his father was a Talmudic scholar, and his mother supported the family, selling flour and grain. Rothbort showed artistic leanings early, shaping little figures from the dough with which his mother made bread. If he found a pencil, he would draw on whatever paper was available, sometimes on the inside cover of a book, an act for which he remembered being punished by the rabbi. His activities gained him the Yiddish nickname Schmuel der Mahler (Samuel the Painter). He was entirely self-taught and never had formal artistic training.

Revolution was in the air as the new century arrived, and as a young man Rothbort was associated with the Bund, a Jewish socialist group which was implicated in anti-Czarist agitation. In 1904 it became prudent to immigrate to the United States, where he worked as a night watchman and began to pick up freelance jobs as an artist, painting flowers, birds, and cherubs in murals for homes, halls, and movie theaters in and around New York. In 1909, newly married, he attempted to be a dairy farmer in the Catskills.

Whether his artistic urges overwhelmed his farming skills is impossible to say, but within two years, Rothbort and his wife were back in Brooklyn. Back home, he participated in group exhibitions and acquired a patron in Hamilton Field, who wrote well of him in The Arts, a magazine he had founded, and presented Rothbort’s work in shows at Ardsley Studios, an exhibition space in Field’s home. Field’s death in 1922 deprived Rothbort of an important connection, and in 1925 the artist and his family moved to Uniondale, Long Island, where Rothbort attempted to be a chicken farmer. Rather, his wife did most of the farming, while Rothbort devoted most of his time to his art. When money was tight (which was almost always) he made art from whatever he could find – watercolors instead of oils, sculpture carved from found stone, driftwood, or fenceposts. He and his family made do for about ten years, and then it was back to Brooklyn, where for years he exhibited his paintings and sculpture in what he called his Home Museum of Direct Art.

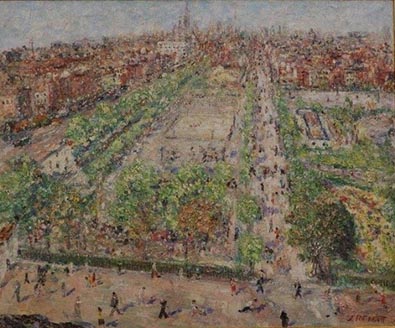

Rothbort found his subjects in the daily life of the city, in a square, for example, like Tomkins Park:

He also took artistic pleasure in his growing family, though with a Rothbortian twist. In Dolls Reading, he depicts his daughter Ruth’s dolls, but without the little girl herself. One doll reads to the others, a subject perhaps inspired by that forebear of Surrealism, James Ensor.

Rothbort’s return to the city coincided with a period of great interest in self-taught artists, an interest influenced by Surrealist beliefs in the spiritual truth of artists who supposedly drew their inspiration straight from the unconscious. It was a time when Grandma Moses, Morris Hirshfield, and John Kane all came to art world attention. Rothbort could not claim to be quite as “naïve” as any of those artists, as he had participated in many exhibitions over the years, but in 1940, the same year that Moses had her first one-person show, Rothbort joined Charles Barzansky Galleries, with whom he would exhibit for the rest of his life.

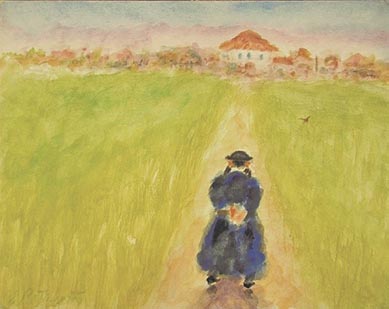

Now entering middle age, Rothbort could finally devote himself unstintingly to his art. He never got rich, but he got by. In the late 1930s and the 1940s, perhaps driven by the Nazi persecution by of Jews in Eastern Europe, Rothbort painted remembered scenes from his childhood — weddings, holidays, market days, farmers, cantors in temples, yeshiva students, drunken Cossacks, all the life of the shtetl.

These works would later be the subject of a 1960 documentary, The Ghetto Pillow: Memories of the Shtetl by Harriet Semegram. This film and the Rothbort images it featured became the major visual resource for the designers of 1964 Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof.

The above, in a nutshell, is an account of an artist who was seemingly tapped for his vocation in childhood and who remained true to his calling. His work, like that of most prolific autodidacts, is uneven – I’ve sometimes thought that if you could get hold of everything Rothbort did and burn about half of it, his critical reputation would stand much higher (though perhaps this is true of most artists, trained and not). But it’s one man’s vision, and it’s a compelling one. It’s also affordable. I’ve posted several works in the “Art for Sale” page of this website. Take a look, and let’s talk.