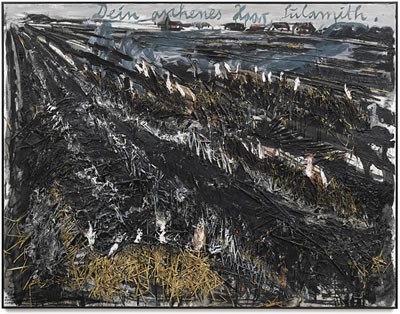

There was a kerfuffle in the art world recently about an exhibition that opened in Beijing last fall and is currently on tour to three other Chinese museums. The exhibition is of the works of Anselm Kiefer (born 1945), a German artist whose monumentally-sized works deal with the heritage of 20th century Germany and in particular with its Nazi past. Kiefer’s works have brought three and a half million dollars at auction, and he is rightfully recognized as one of the most significant contemporary German artists.

Kiefer had had many one-person exhibitions at major museums over the past 30 years; what made this exhibition notable was that over ninety percent of the works were owned by one Chinese collector and that the artist was not consulted in the preparation of the exhibition. The Chinese museums and the German foundation that organized the exhibition dispute that last assertion, but let’s assume that it’s correct and that the artist was given no chance to have a say in the show.

Living artists have traditionally had a hand in museum exhibitions of their works, consulting with the museums’ curators on the selection artworks, working with the museums’ designers on the layout of the galleries, and giving interviews to the scholars writing the catalog. The three galleries which sell Kiefer’s work put out a joint statement that “to plan such an important showcase in China without the artist’s input is disrespectful.”

Whether organizing the show was disrespectful or not, Kiefer and his dealers had no legal standing to block it. The works are the property of the collector, who can show them wherever and however she wants. But the matter is an interesting one, philosophically – what rights does an artist have in the way his or her works are presented?

Any artist wants his or her work to be shown to best advantage and in a context respectful of the artist’s intentions. Living artists can refuse to participate in exhibitions for any number of reasons. Georgia O’Keeffe, for example, declined to participate in exhibitions composed exclusively of works by women artists. She didn’t want to be regarded as a great woman artist; she wanted to be known as a great artist, period. Other artists are leery of having their work pigeonholed as belonging to a specific ethnicity or movement. To categorize is by definition to limit.

Yet artists can be maddening (to us dealers, anyway) with their demands. Clyfford Still was among the foremost in this regard. He went long periods without shows, unwilling to cede any control to galleries or museums. And his will made the ultimate demand: “I give and bequeath all the remaining works of art executed by me in my collection to an American city that will agree to build or assign and maintain permanent quarters exclusively for these works of art and assure their physical survival with the explicit requirement that none of these works of art will be sold, given, or exchanged but are to be retained in the place described above exclusively assigned to them in perpetuity for exhibition and study.” It was a tall order, and it prevented the works in his estate from finding a home or even being seen for a quarter century. The city of Denver accepted the gift and its requirements in 2004.

Well, Still’s finally gotten what he wanted. Will his iron hand maintain its grip for even fifty years? Whether a dedicated museum will burnish his reputation any brighter than it would have been otherwise is open to debate, and whether you think the artist now smiles down on his art from a cloud is contingent on your beliefs in the hereafter.

I myself think that it’s generally a good thing to allow artists a say in the display of their works while they’re alive; it’s wise for the maintenance of a future relationship between them and the museum or gallery, if for nothing else. But I think it should end there. Hung in august silence on museum walls or hidden away in a closet, works of art in the end are independent of the hand that created them. Each viewer will have his or her own reaction to the work, whatever any accompanying scholarly apparatus may say. Give these children your blessing, Artist, and let them go. Like flesh-and-blood children, sooner or later they will have to find their way on their own.