No artworld topics this month. But here’s an article I published five years ago in The Country and Abroad magazine. It’s relevant to a time of year that is always dark, but this year seems darker than usual.

Photo courtesy Wikipedia Commons

On December 21, a few years back, I attended a Winter Solstice celebration. The leaders of the celebration were a bespectacled, self-identified Native American, who looked and dressed like everyone else except for the birch-bark headdress he was wearing and the drum he carried, and an English woman wearing a bird costume. They were well-meaning sorts, but I soon left the ceremony and came home feeling disappointed. That evening I pondered the winter solstice and what it means to us today.

There’s no denying that the shortest day of the year can arouse something deep within us. For thousands of years, our ancestors gathered to perform celebrations designed to acknowledge the darkness and pray for the light’s return. Basically, we’re all a bunch of primates terrified that the sun is going to disappear forever. But there is also a deep urge to feel our old selves die with the old year and be reborn in the lengthening days to come.

It is a fact that we cannot enter into the mindset of our prehistoric ancestors. You can pick up a bow and arrow and run through the woods wearing nothing but a loincloth and moccasins, but you’re not the same as the Native American for whom it was a matter of life or death whether he killed that deer. In the same way, as I stood with the crowd at the solstice celebration, seeing the flashes from cell phones capturing the ceremony and hearing the sound of cars whizzing by, the attempt to recapture Native American or Celtic religion seemed as bogus as the hey-nonny-nonnies warbled by “buxom wenches” at Ye Renaissance Faire.

Yet religious tradition speaks to something deep in us, whether we identify with one of the established religions or not. As Carl Jung taught, the fact that something is a myth does not necessarily mean that it’s not also true, at least on some level. Whether you believe that religion was invented by humans or instituted by God (or gods), the need it speaks to is a powerful human need. Even in our Post-Modern era, when we can easily find ourselves participating in a ceremony and critiquing it at the same time, there is a longing to feel ourselves grounded in something larger than ourselves.

Winter solstice can be a time for reflection, and a ceremony can help to focus on the impulses, desires, and needs that surface at this period. Accordingly, I’m laying out some ideas for such a ceremony. I intend these only as suggestions; you should make whatever adaptations might make the ceremony more meaningful for you. I think a solstice ceremony would be most meaningful when held in the company of friends and loved ones. We all need community, and we need it most when things are darkest, whether literally or metaphorically.

I think the ceremony would be most meaningful when held out of doors, where we experience the reality of bonfires confronting cold and darkness, but if that is not possible, the ceremony could be adapted to candles in a darkened room and could be conducted by one person alone. These things said, here is my outline for such a ceremony.

Lay out four fires in a diamond conforming to the four cardinal points – North, East, South, and West. A fifth fire will be made in the center of the diamond. Make the fires as big or as small as you want. Some people may prefer wood that has been gathered from a place meaningful to them; others may make do with boards left over from a home repair project. Some may conduct a ceremony for the making of the fires, stacking the logs slowly and mindfully; others may simply pile up lumber, squirt it with lighter fluid, and toss on a match. There is no orthodoxy here — do what works for you. By each fire, you should have a bowl containing the item for that fire, which I will discuss below.

Gather your group around the eastern fire. East, the direction from which we see the sun rise each day, has always been symbolic of new beginnings. The bowl for the eastern fire should contain sprigs of dried sage, an herb used in many traditions as a purifying element. At this time of year, we often feel the need to purify ourselves and be born again. Sometimes this takes the form of New Year Resolutions – “I’ll work harder, I’ll lose 30 pounds, I’ll quit smoking.” – resolutions that seldom last outlive winter. At the ceremony I envisage, the bowl is passed around to the people attending. Each person takes a sprig of sage, smells it, and tosses it into the fire. As you do, think about something old that you want to leave behind and the new life you want to live. Avoid grandiose schemes; just take one small thing that you can really do, and vow to cultivate it this year. If you wish, you may speak your vow out loud to the group, but such disclosure shouldn’t be demanded. There are a lot of old demons we should cease to feed – old resentments, old fears, old ways of behaving. Standing at the eastern fire, we should encourage ourselves to let them die with the old year.

Move on to the southern fire. In our hemisphere, warmth comes from the south, the warmth we look forward to when spring comes. Warmth is identified with love, with growth, with good things ending in harvest. It is literally the first sensation we feel, naked in our mother’s womb. The bowl for this fire should contain tobacco. I would get an aromatic pipe tobacco, but that may be simply because I associate the smell with my grandfather. As the bowl gets passed around, each person takes a pinch of tobacco, sniffs it, and tosses it into the fire. As we do so, we should reflect on love and the other blessings of life. And we are blessed, worry about the bills and the difficulties of life as we may. Life is good. Standing at the southern fire, we should be thankful for the miracle of being alive.

At the western fire, we should remember our dead, particularly those people we have lost in the past year. Humans have always associated the setting sun with the end of life. In World War I, when a soldier was killed, his friends would say that he had “gone west.” “Here’s rosemary for remembrance,” Ophelia says in Hamlet, and the bowl for the western fire should contain sprigs of that herb. The poet Ted Berrigan wrote wonderfully about how a loved one passes from our outside life to inside. “Slowly the heart adjusts to its new weight,” he said. As we stand by the western fire, each person sniffing a sprig of rosemary and tossing it into the fire, we should reflect on our departed loved ones, our “good dead,” perhaps speaking their names aloud, and feel their lives now carried in ours.

Next, the northern fire. The far north has always seemed inhuman, hostile to our species. It is from the north that the cold winds come to freeze us. At the northern fire, we reflect on a universe in which our beings seem tiny and unnecessary. The bowl for this fire should contain pine, whether in the form of resinous sticks or pinecones. The items at the other fires are taken into our bodies, whether by eating or inhaling. Pine symbolizes the nature that remains outside us and does not need us. We are not masters of all existence, and we should remember that fact as we stand here.

Finally, we move to the central fire. I can’t think of a bowl for this fire, though you might come up with one. Perhaps it is simply enough for us to stand around this fire and try to sum up the emotions the other fires have aroused in us – the hope, the thankfulness, the remembrance, and the sense of how tiny we are, as we stand on this blue speck circling a small star rotating around the center of one of an uncountable number of galaxies. Yet tiny as we are, we are here, and we play our part in the grand scheme of things. “You are not a drop in the ocean,” Kahlil Gibran said, “You are the ocean in a drop.” And so we are, as we say a prayer, extinguish the fires, and head our ways home, separately or together. God bless us, every one.

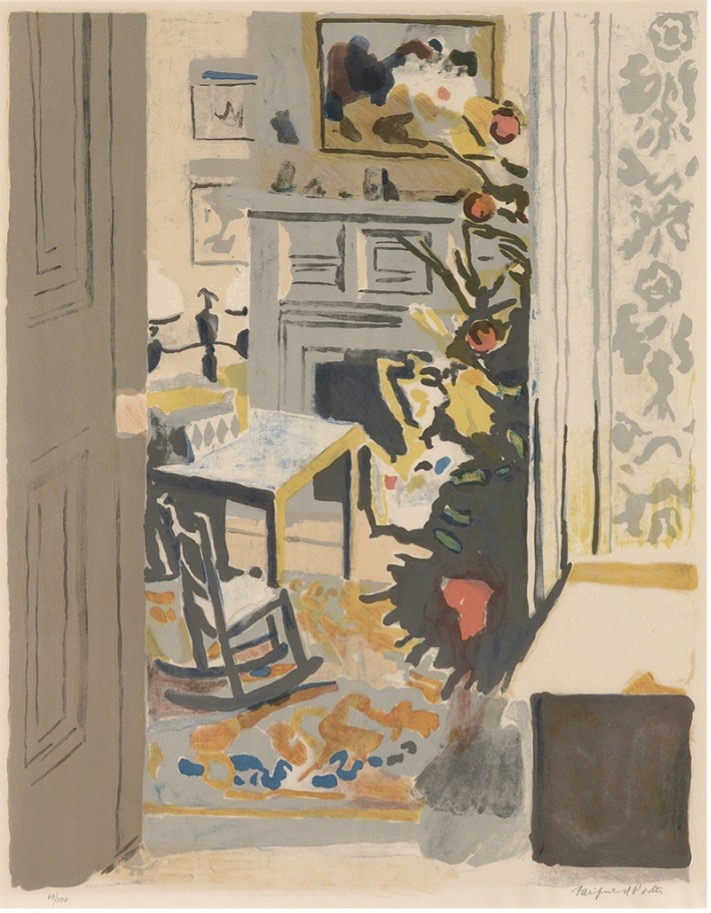

Fairfield Porter. The Christmas Tree, 1971. Color lithograph.