“The art business is not something you can equate to any other business. They’re not selling stocks and bonds here. They’re selling fine art.” Thus spoke dealer Helly Nahmad in a recent New York Times article entitled “The Fickle Salesroom,” which reported on a 40 percent drop in sales of impressionist and modern art at auction this November, compared with the sales of six months ago.

The art market may not be like the stock exchange, but that’s not for want of trying. At the annual meeting of the Appraisers Association of America a couple of weeks ago, I heard speaker after speaker talk about new realities in the art world, several of which are attempts to wrestle an unruly market into something with which an investor can be comfortable. The situation has long been in the making.

In 2002, the Mei Moses Indices were developed by two Stern School of Business professors. These indices attempt, in the words of Sotheby’s, which acquired the company three years ago, to produce “objective art market analysis to complement the world-class expertise of [Sotheby’s] specialists.” Sotheby’s goes on to explain that “the Sotheby’s Mei Moses indices control for differing levels of quality, size, color, maker, and aesthetics of a work of art by analyzing repeat sales.”

It sounds all very scientific, but I have my doubts. As has been pointed out by critics, indices such as Mei Moses overstate return and underestimate risk. For one thing, most art sales don’t make it into databases such as Artnet or Askart, as they’re made privately. Second, repeat sales at auction account for less than 2% of all sales, and the repeat sales reported in the databases are subject to what economists call “survivor bias” – only the successes generally make it back onto the market.

As an example, let’s say you bought paintings by two contemporary artists, John Doe and Richard Roe, for $10,000 each at auction in 1999. Now you’ve decided to sell them at auction, and you approach Sotheby’s. John Doe has had a stellar career since 1999. There have been a couple of museum shows that have been very well received critically, and Doe has been picked up by one of the mega-galleries – Gagosian, Zwirner, or the like – who are hyping him to beat the band. Of course Sotheby’s will be happy to offer your John Doe, and let’s say it sells for $40,000. That repeat sale gets noted by Mei Moses – a 400% return in twenty years! – and it skews the statistics. Contemporary art is a sure-fire bet!

But what about the painting by Richard Roe? Roe hasn’t had a great career since you bought his painting. He’s had some drinking problems, critical interest in him has slackened, his old dealer retired, and no other gallery has picked him up. When you take his painting to Sotheby’s, they advise against offering it. It’s just not important enough anymore, and you’re going to take a haircut if you try to sell. So the painting doesn’t come up at auction, and the indices do not reveal the bad buy, investment-wise, that you made.

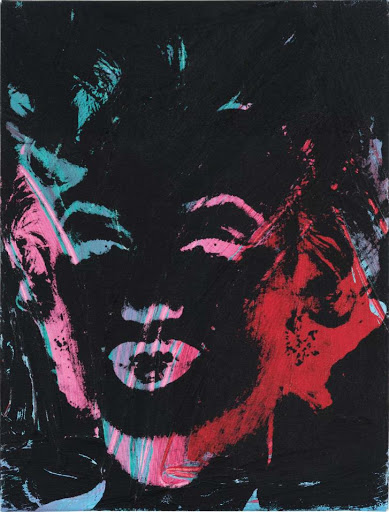

Yet people continue to attempt to make the monetization of art a predictable and safe investment. There’s an artificial intelligence company now attempting to gather “non-traditional” data via social media posts, museum shows, and the like to give investment ratings to artists who don’t have an auction record. Another company called Masterworks, LLC offers small investors to buy shares in a work of art through blockchain technology for as little as $20 a share. Masterworks, LLC recently bought Andy Warhol’s “1 Colored Marilyn, Reversed Series” for $1.8 million.

Masterworks’ Chief Financial Officer says that the company has gotten SEC approval to offer such shares, and the work will eventually be sold. From what I gather, a sale must be made within ten years and can be made only after approval by a majority of the shareholders.

It sounds crazy, but I’m not going to predict that it won’t work. Twenty years ago, I would have confidently asserted that no serious collector would buy a work he hasn’t seen in the flesh. Who would buy a pig in a poke? Nowadays, however, according to the head of Heritage Auctions, 80% of their offerings are sold online to people who have seen the lot only through images. I can understand that trend when buying baseball cards or coins, which are graded by independent authorities and come sealed in tamper-proof packaging. I can even understand image-only bidding when buying at furniture auctions – smartphone camera technology today means that a prospective bidder can easily receive a whole slew of high-resolution images documenting every detail in the piece, including maker’s marks, old labels, scratches to a surface, and any repairs that have been made over the years.

But what about paintings? An image will reveal the basic facts of the piece – its subject, composition, and (if the photo is accurate) its colors. The photo can’t show the impasto of the brush strokes, however, and how they will catch the light at different times of day in your home. Perhaps that matters less and less. We’ve become a culture of sight, not touch or texture, and technology has improved to simulate three-dimensionality. We have long had the ability to photograph an original painting and then print the image on a new canvas with more-or-less perfect fidelity. Now, with the advent of 3-D printers, we can scan an original work of art and reproduce it on a new surface, simulated brush strokes and all.

Some collectors have made use of this technology. One of the speakers at the AAA annual meeting, an art and investment advisor, told of clients of his who had had their collection reproduced with modern technology so that they could enjoy their paintings (or at least their simulacra) in their home in Palm Beach, their pied-a-terre in New York, and their ski lodge in Aspen.

Yet for most people, something like magic still hovers around an original work of art, in their knowing that this object was made by a person who once lived and breathed. The magic can draw crowds of people, as visitors to the Mona Lisa are well aware.

What if the guard in front of the painting informed the crowd that the object they were desperately trying to capture with their smartphones was a perfect simulacrum and that the real painting had recently been deemed too precious to be exposed and was now being stored in a bomb-proof vault in the basement? He could assure the visitors that the reproduction on display was identical to the original and that it had been placed in the painting’s original frame, behind glass, as the real painting had been. The experience of visiting the painting, visually, was just the same as it ever was. Not even scholar-experts, standing where the visitors were standing, would be able to tell that they weren’t looking at the real thing. Would the crowd stick around? You know the answer as well as I do.

Over 70 years ago, the philosopher Walter Benjamin asserted that “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: Its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” Reproductions of a work of art, Benjamin thought, diminish the aesthetic value of the original by changing the cultural context of the piece. Techniques of reproduction today are light-years ahead of techniques when Benjamin wrote his essay, and images are everywhere in this Age of Instagram. Yet face-to-face with an original work of art, we still feel some kinship, whether conscious or not, with the person who created it.

Henry James spoke of “the madness of art.” Let’s do something as crazy and old-fashioned as art is: let’s talk, person to person. Call me.