I once interviewed the artist Philip Pearlstein, who is well-known for his paintings of nudes. As a child growing up in Pittsburgh, Pearlstein was encouraged in his artistic leanings by his parents, who sent him to Saturday morning classes at the Carnegie Museum of Art. In 1942, at the age of 18, he won an art competition sponsored by Scholastic Magazine, and two of his paintings were reproduced in Life Magazine. He enrolled in the Carnegie Institute of Technology the following year, but World War II was raging, and Pearlstein was soon drafted into the Army for the duration. He ended up in Florence, Italy, painting road signs for truck convoys.

Released from the service, Pearlstein resumed his studies at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, where one of his classmates was a pasty-faced 18-year-old named Andy Warhola, who would later drop the final letter from his last name. Pearlstein and Warhol became friends, and when the younger man learned about Pearlstein’s winning the national art competition four years earlier, he exclaimed, “Gee! You were famous!” “Yeah,” replied Pearlstein, “for 15 minutes.”

Pearlstein looked at me, his interviewer, and added sardonically, “And that’s where it came from.” He was referring, of course, to Warhol’s much-quoted saying, “In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.”

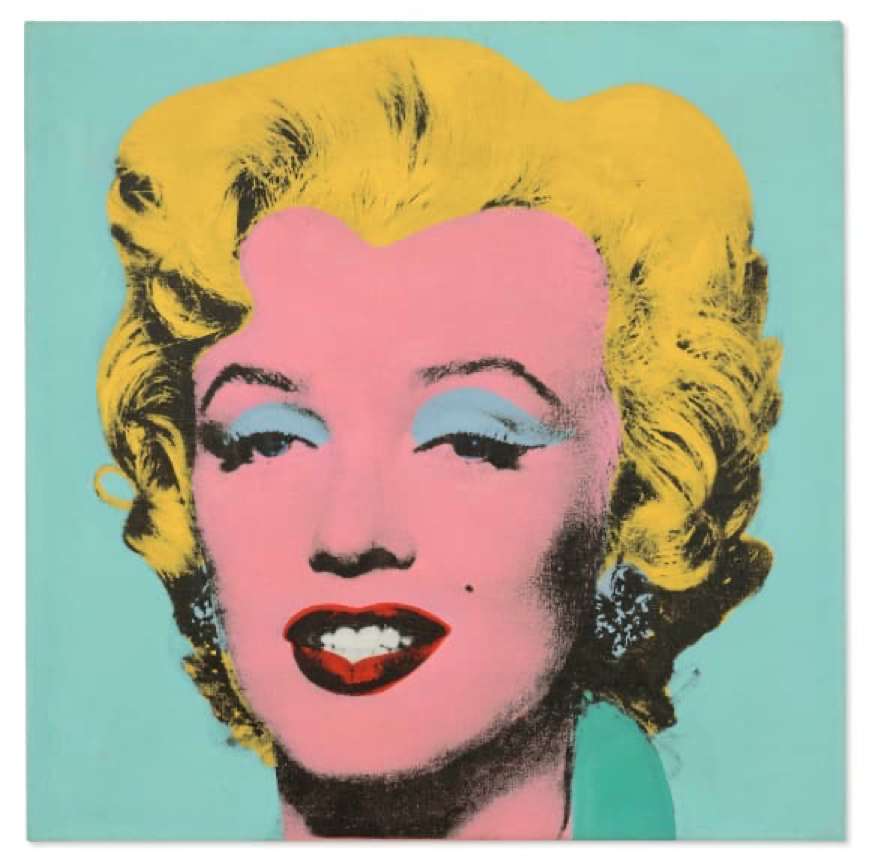

I have been thinking about Warhol lately for two reasons. The first is the Netflix series The Andy Warhol Diaries, an entertaining if ultimately sad series that presents the artist as world-famous and yet unable to find the lasting love he privately longed for. The other reason is the upcoming sale (May 9) of one of Warhol’s iconic paintings of Marilyn Monroe, Shot Sage Blue Marilyn at Christie’s.

Christie’s online catalogue says “Estimate on Request” regarding the painting, but it has been widely reported that Christie’s expects the work to bring as much as $200 million, eclipsing the previous Warhol record at auction of $105.4 million set by Car Crash (Double Disaster) in 2013.

Warhol used photographs of everyone from Marlon Brando to Liza Minnelli in his paintings, but the Big Three, in terms of desirability, are Elvis Presley, Jackie Kennedy, and Marilyn Monroe. It could be argued that, of the three, Marilyn is numero uno. She died, still beautiful, at the height of her fame and remains a symbol of sex appeal in a way that Brigitte Bardot, her near contemporary who is still alive, has not.

The upcoming sale has Christie’s spokespeople hyperventilating. Alex Rotter, the chairman of their 20th-21st Century department said, “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn is the absolute pinnacle of American Pop. The painting transcends the genre of portraiture, superseding 20th century art and culture. Standing alongside Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and Picasso’s Les Demoiselle d’Avignon, Warhol’s Marilyn is one of the greatest paintings of all time.”

Botticelli, Da Vinci, and Picasso – that’s some company to stand beside. I don’t know if I’d go that far, but all auction houses (and dealers) engage in bombastic hoopla at times, as when five years ago Christie’s touted a portrait of Christ recently attributed to Da Vinci as “the male Mona Lisa.”

Whether or not Warhol is fit to rub elbows with Da Vinci et al., there’s no doubt that he is now more influential that he was at his death. His quip about 15-minute fame seems incredibly prescient in the age of Tik Tok and Instagram (which everyone who knew Warhol says he would have loved). His unabashed queerness, his gender-bending, and his embrace, at once admiring and ironic, of fashion and popular culture permeate contemporary art and may well be America’s most influential export. You may love Warhol or hate him, but you can’t get away from him.

It strikes me that to use the words “love Warhol” and “love Warhol’s work” as interchangeable terms acknowledges an inseparable connection between the two that I would grant to few other artists. I had a professor in grad school who said, “What Andy Warhol is, is as important as what Andy Warhol does.”

“How can you say that?” I argued. “In 50 years Warhol will be dead, and his works will have to stand on their own. His persona won’t matter then.” In time, however, I came to see Warhol as analogous to Oscar Wilde, another artist with an outrageous persona which became inseparable from the art he made. Or rather, his persona was just another piece of the art he made.

A persona can help the appreciation of an artist’s work or hurt it – just look at Salvador Dali making the rounds of late-night talk shows, his artistic reputation diminishing in an inverse relationship with the length of his mustache. And an artist without a persona can do just fine – look at Philip Pearlstein, who created a substantial body of admirable work that is safely ensconced in museum collections today. But a Pearlstein painting of an anonymous model won’t sell for $200 million. Andy and Marilyn – a perfect storm.