As we watched the news of the deep freeze in Texas, our horror at the images of people burning furniture to stay warm and lined up for hours trying to buy food was made doubly shocking, whether we realized it or not, because of the unconscious perception most of us carry around of Texas as a broad-shouldered, can-do state, tough as an oilfield roughneck. Texans themselves carry a sense of being larger than life and will miss few opportunities to demonstrate it.

In the art world, nothing symbolized this Texan self-aggrandizement more than the Western Heritage Sale, an annual event from 1975 to 1985 that was held at the world-famous Shamrock Hotel in Houston. A black-tie affair, hosted by former Governor John Connally and some of his friends from the oil patch, the sale had alternating lots of contemporary cowboy art, thoroughbred horses, and prize-winning Santa Gertrudis bulls. (They didn’t sell the actual bulls, just “straws,” as they are called, of the bulls’ semen.)

The bidders at the Western Heritage Sale may have been as expensively-coutured as attendees at one of the evening Impressionist sales at Sotheby’s or Christie’s in those days, but any resemblance ended there. Attending the Western Heritage Sale, I always found the greatest cognitive dissonance in the spectacle of elegant ladies sipping champagne as they strolled between livestock pens, the odor of manure overpowering the delicate scent of expensive perfumes.

Once inside the ballroom, attendees were seated at banquet tables, and the liquor flowed freely. At New York art auctions, the auctioneer calls the bids in a plummy voice, “One million. I have one million. Do I hear a million one? Thank you, Madam.” At the Western Heritage Sale, the auctioneer was a livestock auctioneer, using the same call he would use to sell prize pigs. “Ho! Twentyfivetwentyfivetwentyfive! Where’s the bid?” he would chant while his pitmen shouted bids up at him from the floor. He would cajole his audience in every possible way, including humor – “Hey, Charlie! Are you gonna let Bill have this painting after what he did to your WIFE?”

Record prices were routinely set at the sale for contemporary painters of cowboy scenes, but the alcohol-fueled bidding meant that such records needed to be taken with a whole bagful of salt by the art market. “It’s just a bunch of Texas oilmen money-whipping each other,” sniffed a Texas dealer to me. “You could take them a better painting a week later for less money, and they’d throw you out of their office.”

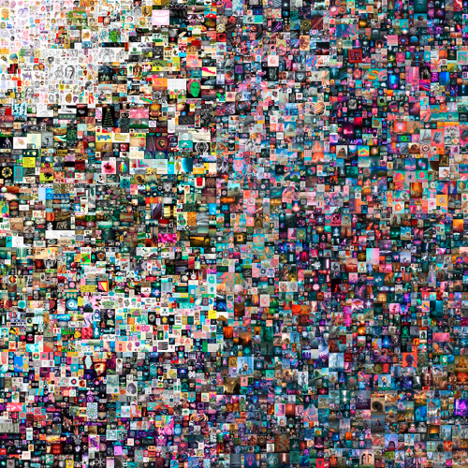

The excesses of those days were brought to mind by an auction that is taking place as you read this blog. Starting February 25, Christie’s began offering an NFT-based work of art entitled “Everydays: The First 5,000 days” by Mike Winkelmann, also known as Beeple.

Beeple is a big deal in the world of digital artists. He has over two million followers on Instagram and has created graphics and videos for stars such as Justin Bieber and Katy Perry as well as for brands such as Nike and Louis Vuitton.

If you’re a dinosaur like Reagan Upshaw, who is still routinely amazed that the words he types into his laptop can magically fly through the air to his printer, please be advised that he is attempting to explain a concept that he doesn’t fully grasp. NFT stands for Non-fungible Token, in this case for a digital work of art. This unique digital token is encrypted with the artist’s signature and is individually identified on a blockchain (a term you can look up in Wikipedia; I’m not up to trying to translate). In effect, it verifies the title holder (owner) of the work and guarantees the work’s authenticity. In other words, it makes digital artworks unique. NFTs can be bought and sold, and the blockchain technology they run on allows their ownership and authenticity to be tracked.

The artist Edward Kienholz once created a work of art that was nothing but a contract. The contract stated that the contract itself was the work of art by Edward Kienholz and that, since most collectors are only engaging in glorified autograph collecting anyway, this work of art had the advantage of being easy to transport and display. More recently, the artist Maurizio Catallan caused a furor when he sold a banana duct-taped to a wall as a work of art. Or rather, he wasn’t just selling the banana – he was selling the idea, a set of instructions, and the right of the new owner to recreate the work. In some ways, this is analogous to “Everydays.”

Once the auction ends, the NFT becomes to the winning bidder’s property, encrypted with his or her information. It can be displayed on a computer screen, or the image can be printed out and hung on a wall. Other people might be able to make a digital copy of the work, but without the NFT, the copy has no value.

This is actually not a new concept. The minimalist sculptor Carl Andre became famous 50 years ago for his floor sculptures consisting of square metal plates arranged to form a larger shape. Such plates were easily obtainable by anyone. After a dispute with a museum about the placement of one of his sculptures owned by the museum in an exhibition, Andre announced that he was withdrawing his authorship of the piece. He recreated the sculpture in his studio, gave it the same name, and told the art press, this is the real sculpture – what the museum owns is just some metal squares. They don’t have a sculpture by me.

But back to Beeple. In Christie’s sale, which runs through March 11, bidders will be able to use bitcoin to bid online, but a credit card will also suffice. The bidding started at $100 and had jumped to $1 million within an hour. (It is $2.5 million at the time I am writing this.) What does the bidding frenzy mean for the art market? As the online magazine The Canvas puts it, “Until now, collectors in [the NFT field] seem to have been mostly attracted to the bragging rights that come along with spending an objectively absurd amount of money for works of art that don’t even exist in the physical realm and often amount to no more than screenshots or blurry, pixelated images. And it’s hard to deny that a large subset of this market comes down to young, mostly male, ‘crypto bros’ who have made obscene amounts of money as the value of bitcoin rose exponentially over the past year, having little else to spend their digital fortunes on.”

As with the prices paid by the buyers of cowboy art in Houston 45 years ago, the prices paid in NFT auctions may have no basis in reality. But then, what is reality in these days of cryptocurrency and virtual art? It’s a brave new world out there. (I’m staying home.)