Summer normally brings family parties on the deck for Roberta and me, and at a recent such get-together I was talking with my nephew Greg, about whose boyhood enthusiasm for collecting baseball cards I have written. Greg, now middle-aged, long ago put his baseball cards aside and now collects illustrations and other collectibles from popular culture. He has a particular fondness for Batman.

Greg had read my blog about baseball card collecting in 2017, and he told me that the advice on collecting that I tendered then still guides his collecting. “Guys at work know that I collect this stuff, and they’re always asking me, ‘Greg, I have a chance to buy a Superman action figure for $25.00. What do you think? Will it go up? Is it a good buy?’ I always tell them that nothing is guaranteed to go up. If they like something and want to live with it, they should buy it, but forget about trying to buy low and make a killing later.”

He went on, “I have some very nice things that I enjoy living with. I paid top dollar for them, to get the best. I never intend to sell them, so it doesn’t matter what happens to the market.”

Top dollar in Greg’s case is very much below top dollar for works by important contemporary artists, but collecting principles should remain the same. Alas, too many people – I won’t call them “collectors”; they’re the artworld equivalent of day traders – haven’t read my blog. A recent front-page article in The New York Times by Zachary Small and Julia Halperin detailed the woes of some artists in their 20’s who had the misfortune to become very hot. Why was that a misfortune? Because speculators, dealers, and art advisors began buying their works like crazy. The artists responded by pumping out a lot of art. Then their buyers sold, taking a quick profit, and the bubble burst.

(Hit a paywall on the NYT article? Read an unrestricted version here).

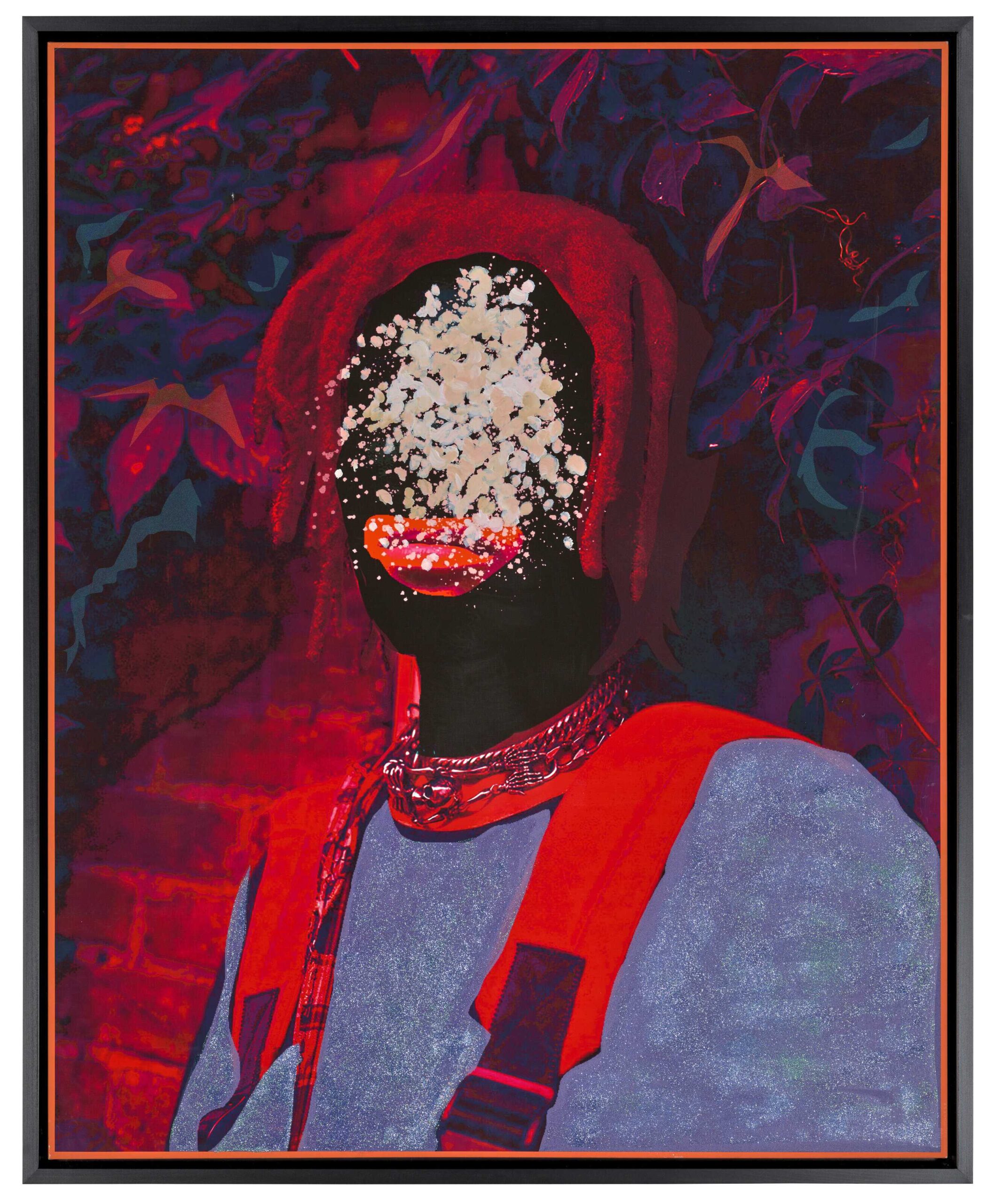

The market for works by artists of color has been extremely hot in recent years, and three of the four artists profiled in the Times article were artists of color. The other was a woman, also a hot market these days. Amani Lewis’s story was typical. Five years ago, they (the artist’s pronoun) were a well-regarded young artist whose works sold in the low five figures. Then the fickle finger of fate tapped Lewis as a soon-to-be star, and their works started bringing six figures. The culmination of their rise at auction came in November of 2021, when Into the Valley, The Boy Walks (Psalms 23:4) sold at Phillips in New York for $107,100 including premium. They were, to use an old expression, hotter than a two-dollar pistol.

Amani Lewis, Into the Valley, The Boy Walks (Psalms 23:4), 2020

Mixed media on paper, 68-1/4 x 55 inches. Photo courtesy Askart.

But things were too hot not to cool down. In late 2022 and 2023, several of Lewis’s works at auction didn’t sell (they were “buy-ins,” to use the trade term). Other works sold well below estimate. The early flippers had taken their profits, and current owners had begun to feel that their “assets” were losing value. They were desperate to dump the works and recoup at least some of their money. The culmination of this death spiral came a couple of months ago, when Into the Valley was sold for $10,080 including premium at Christie’s. That’s a ninety percent loss in value in just two years.

It’s a sad story for the artists, but not a new one. I wrote about the same subject eight years ago. Such booms and busts are inevitable in a market where the thing being sold has no inherent value but only the value its buyers assign to it. Sometimes those buyers go crazy.

As an appraiser, I sometimes have the happy occasion to tell clients that the works they acquired years ago are now much more valuable. Other times, however, I have to tell clients that the market for the works they have acquired has declined. It’s a cold, hard business – sentimental feelings, whether on the part of the client or the appraiser, have no role in it. I have to determine what a particular work was worth on a particular date, such as the date of the owner’s death, the date the work was given to a museum, or some other date. Nothing else matters.

But if those buyers bought things they loved, as my nephew does, then they had the privilege of living surrounded by things that gave them pleasure. That pleasure can’t be taken away, no matter what the market does.