A reader of this blog recently sent me an article from Bloomberg News entitled, “Prices of Contemporary Indigenous American Art Have Risen Over 1,000 Percent.” That statement is undoubtedly true, although, as with all “hot” tips on Wall Street, by the time the tip reaches the general public, insiders have already made their profit and moved on. New buyers will pay much higher prices. The savviest contemporary collector I know transitioned his buying from Black art to Native American contemporary art at least three years ago.

It’s easy to get cynical about the art market. Is Native American contemporary art just the new Flavor of the Month? With art, there is no inherent demand. You have to eat; you need someplace to live. Prices for food and housing may go up or down, but there will always be a market. The market for works of art, by contrast, is influenced by any number of things, all of them artificial, no pun intended. Dealers are seeking to get in on the ground floor of the latest thing, trying to create a demand they can stoke. Curators are aware of political concerns as much as aesthetic ones as they try to organize shows that will receive critical approbation while still bringing in crowds. Critics are looking for new movements on which they can make their names. The climate is constantly changing, and art fads can be as short-lived as those of the world of fashion.

After centuries in which art markets and art museums were dominated by white men, hitherto under-represented artists are now being aquired with a vengeance, particularly by institutions. The rise of feminism fifty years ago (and the agitation by the Guerilla Girls and other activists in the 1970’s) started a reassessment of art made by women, and the market began to respond.

The Civil Rights movement of the 1960’s threw light on the exclusion of Black artists from art history, most notoriously in “Harlem On My Mind,” a 1969 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of New York which purported to celebrate the Harlem Renaissance while not including a single painting or sculpture by a Black artist. The situation has changed – Black art has been a hot item in recent years.

The problem is that artistic segregation, self-imposed or imposed by institutions, tends to be limiting to an artist’s career. Does an artist want to be seen in a particular context or as self-standing? Throughout her career, Georgia O’Keeffe consistently refused be part of women-only exhibitions. She wasn’t a “woman artist,” she insisted, she was an artist who happened to be a woman. She knew that, as the Supreme Court in 1954 ruled in another context, separate is inherently unequal.

Categorization cuts both ways. Being included in a group can help shine a spotlight on a young artist’s work, but the problem lies in trying to escape the confines of that group later. In the case of Native American artists, there’s been a “buckskin ceiling” in the art scene.

The Cherokee artist Kay WalkingStick (born 1935), in a recent interview with The New York Times, spoke of ignoring the advice of a dealer early in her career who warned her not to exhibit with other Native American artists, telling her that the resultant pigeonholing would make it harder for her art to reach a broader audience. “Maybe that happened,” she mused. Her work now reaches a wider audience, most notably in an exhibition held last year at the New-York Historical Society, but she has toiled in obscurity for most of her career.

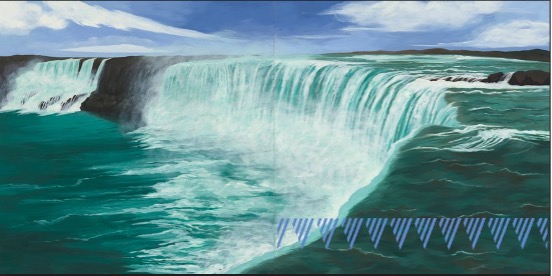

Kay WalkingStick, Niagara, 2022, oil on wood panel, 40 x 80 inches.

Collection New-York Historical Society.

In her exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, WalkingStick’s paintings were paired with works by members of the Hudson River School. The painting of Niagara Falls above recalls Frederic Church’s monumental 19th-century painting of the same subject, but WalkingStick has added geometric patterns similar to those found in indigenous art of the area in a symbolic attempt to reclaim the landscape.

I must say that I prefer Walkingstick’s earlier works to this series. The paint handling of the landscapes seems uninspired to me, and simply adding a few geometric passages doesn’t make the paintings any more interesting. My lack of enthusiasm is not mirrored by the Museum of Modern Art or the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, however, both of which have recently acquired works by WalkingStick. Perhaps I’m just too much of an old WASP fuddy-duddy to truly comprehend the anti-colonization project of her work. It seems like a schtick to me.

Far better, in my opinion, is the work of Jaune Quick-To-See Smith (born 1940), a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, whose recent exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art was quite rewarding. Smith approaches the world and the Native American place in it with a knowing and often ironic eye, but she’s also a truly contemporary artist who wants to take her place in the larger discourse. She takes her inspiration from all sources; for example, she has said that her use of newspaper as a collage element in paintings was influenced by the works of Robert Rauschenberg. I’m not crazy about Smith’s monumental works – with huge size seemingly there for its own sake, they are liable to go flaccid in the handling of paint – but her smaller works are always of interest, and her drawings and graphic work are delightful.

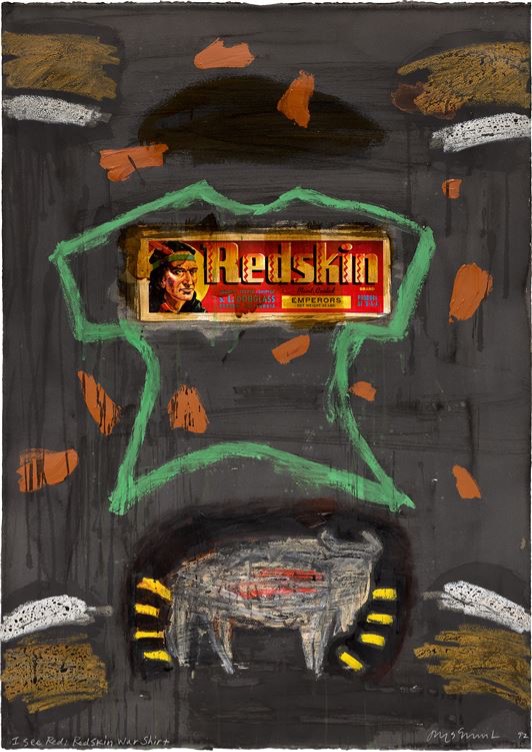

The art market agrees that Smith is the real deal. One of her paintings blew past its $80,000-120,000 estimate at Christie’s in 2022 to set a record of $642,600 including premium. And the craze shows little sign of abating. I See Red: Redskin War Shirt from 1992 sold at Heritage Auctions in Dallas in October of 2022 for a price of $37,500 including premium. The same piece was offered seven months later at Phillips in New York and brought $76,200 including premium.

Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, I See Red: Redskin War Shirt, 1992, acrylic, oilstick, and paper collage on paper, 41-3/8 29-1/2 inches. Photograph courtesy Phillips, New York.

Double your money in seven months! Prices ten times higher in just a few years! But you can’t jump on this bandwagon; it has already left town. I think the market will continue to rise, if at a much more modest rate, but the big players who bought earlier are the ones who made a killing.

There’s art, and there’s the art market. Crazes come and go. Great work escapes the milieu in which it was made to move viewers in vastly different times and places. I suspect that much of the Native American art being snapped up today by museums will eventually find its resting place in their storage racks, but the same could be said of the art of most of their white, Black, Latino, or Asian-American contemporaries. Time will sort things out, but we won’t be here to see it.

In the meantime, I’ll keep my eye on my prescient collector friend. What’s he buying now? Oil paintings by left-handed albinos? Kinetic sculpture by oil-field roughnecks? Watch this space.