Leaving aside the World War II years, which were more than just an “era,” there have been two periods in the past hundred years that have caught the popular imagination. The more recent was the Sixties in America, particularly the Summer of Love in 1968. Psychedelics, shaggy hair, and tie-dye shirts with bell-bottom pants all found their way into mainstream aesthetics and became a world-wide influence.

The other period was the Roaring Twenties. The French called that period les années folles, the Crazy Years, and the center of that craziness was Paris, where French modernists escaping conformity, White Russians escaping Bolshevism, and rich Americans escaping Prohibition made a clean break with the strictures of the preceding war-blasted decade to concoct a heady scene from which emerged a new artistic style – clean, luminous, and merciless – which became known as Art Deco. Two of the best-known practitioners of the style in Paris were from Eastern Europe. One was the noted designer Romaine de Tertoff, better known as Erté. The other, Tamara de Lempicka, is currently the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

Born Tamara Rosa Hurwitz in Poland or Russia in 1898 (her birthplace is a matter of dispute), Lempicka was the daughter of a wealthy lawyer with roots both in Warsaw and St. Petersburg. Raised in Warsaw, she began making art at an early age. At 17 she had a brief term at school in Switzerland, but left to travel with her grandmother on a long tour of Italy, where she became familiar with Old Master art, including that of Bronzino and the other 16th century Italian Mannerists, who would become a significant influence on her style.

In 1916, she met and married Tadeusz Lempicki, a Polish lawyer, and settled in St. Petersburg. The Russian Revolution in 1917 put an end to their privileged life when her husband was arrested by the secret police. He was released after a couple of months, but Russia was not safe, and Tamara and her husband fled, eventually winding up in Paris, where they were joined by other members of her family. They had a daughter, whom Lempicka would later try to pass off as her younger sister.

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait of a Man (Tadeusz Lempicki), 1929

Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne. Photo by Reagan Upshaw.

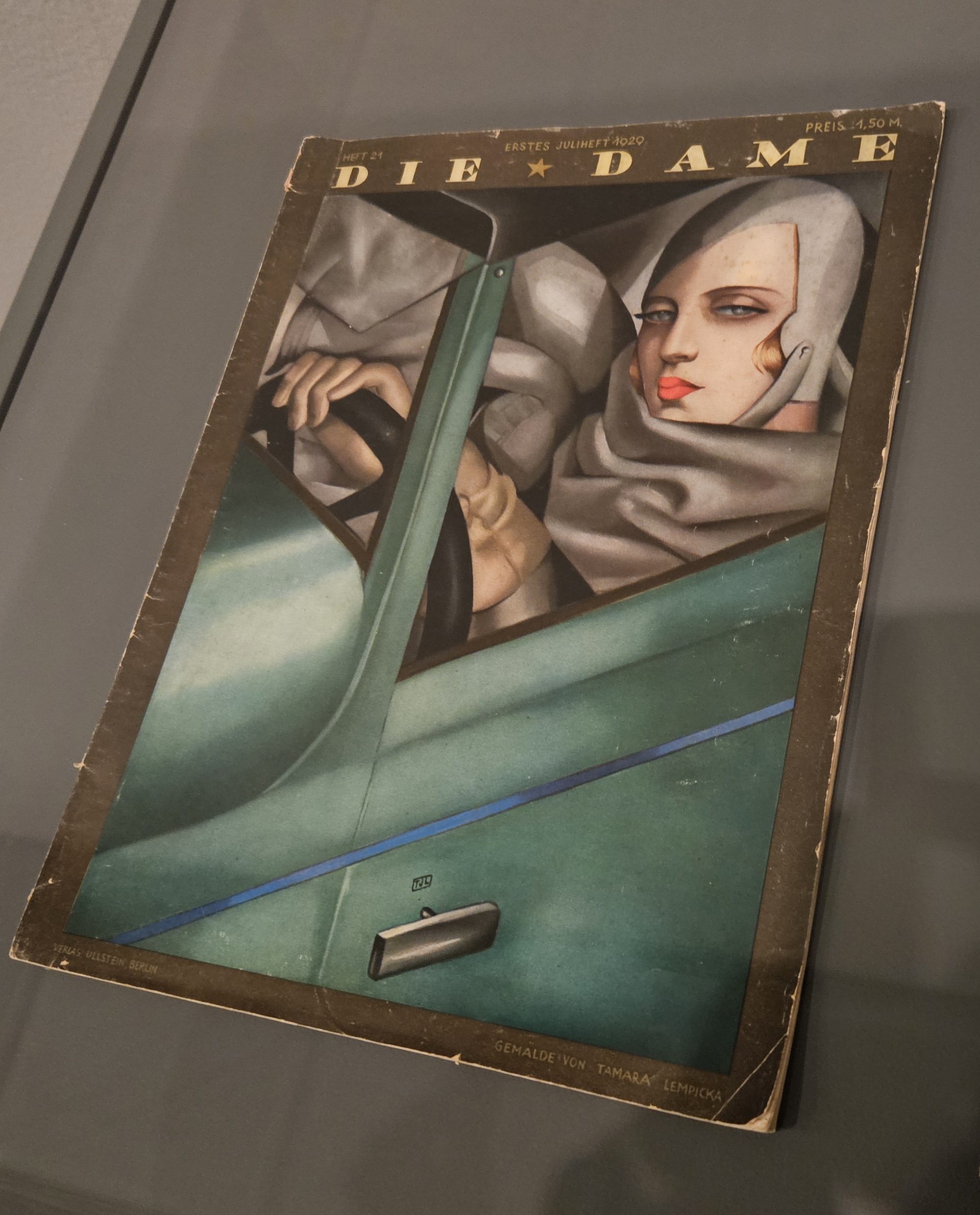

In Paris, Lempicka studied painting with Andre Lhote, a well-regarded teacher who took the discoveries of Picasso, Braque, and others and adapted them into a kind of Cubism Lite, obviously modern but without the radical distortions of his predecessors. It appealed to collectors who wanted to be au courant but were comforted by the traditions of the preceding century. Lempicka took Lhote’s teachings and merged them with her love of the Mannerists, creating an unmistakable style that was widely attractive to the fashion magazines. Her Self-Portrait in a Green Bugatti, reproduced on the cover of the magazine Die Dame (not in the de Young show, although represented by a copy of the magazine), remains probably the most famous painting to come out of the Art Deco period. It is also an example of Lempicka’s carefully curated image – she actually drove a Citroen, not the more expensive Bugatti.

Tamara de Lempicka, Cover for “Die Dame”, July, 1929 issue

Photo by Reagan Upshaw.

Lempicka plunged headlong into the art scene, becoming a sought-after portraitist of Jazz Age society and sleeping with many of her subjects, male and female. Her work was exhibited at several Parisian venues, most notably at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, which later gave its name to the Art Deco style.

Lempicka’s portraits depict sitters well-armored in cash and youth. There is little room for elderly or indigent people in her aesthetic, although there is often a melancholy sense of loss in her subjects, something Lempicka as a (monied) refugee from the East could recognize. A fall from grace could happen any time. A member of the once-proud Romanov family, the Grand Duke Gavril Konstantinovich, for example, wears an Imperial Guard uniform, but there’s no mistaking the fact that his former privileged society is now dead as a doornail.

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait of His Imperial Highness the Grand Duke Gavril Konstantinovich, c.1926

Private collection. Photo by Reagan Upshaw.

Lempicka was a hot artist, but such a lifestyle was bound to take its toll. A chronological label in the de Young exhibition pretty much sums up her domestic situation: “Her homelife is stormy: Tadeusz grows intolerant of his wife’s affairs, cocaine use, late nights spent at clubs followed by valerian-induced sleep, and long work sessions listening to Richard Wagner at full volume.” (Some readers might view the last charge alone as grounds for divorce.)

Shortly after her divorce, Lempicka was commissioned to paint a Spanish dancer, the mistress of a Hungarian baron and industrialist named Raoul Kuffner. By the time the commission was finished, she was in line to become the baron’s next mistress, and she married him in 1934 after the death of his first wife. Thenceforth, she made good use of Kuffner’s title and was delighted when the popular press styled her “the baroness with a brush.”

The Great Depression and the rise of fascism put an end to the heady atmosphere of the Twenties. Always a shrewd observer of the political climate, Lempicka did her husband a great favor by encouraging him to sell his properties in Hungary and move the proceeds to Switzerland. She continued to work, painting portraits of King Alonso XIII of Spain and Queen Elizabeth of Greece, but her eyes were toward the United States, which she had already visited to work on commissions.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, Lempicka and her husband moved to the United States, where they first settled in Beverly Hills in the former residence of the famous director King Vidor. She mingled with Hollywood “royalty” and participated in a 1941 traveling exhibition to raise funds for refugees. One such painting in the de Young exhibition, Escape (Somewhere in Europe), is jarring. It’s technically fine, but after all you have seen, it looks like a movie poster of actors from a heartrending Hollywood film.

Tamara de Lempicka, Escape (Somewhere in Europe), 1940

Musée d’arts de Nantes. Photo by Reagan Upshaw.

Moving to New York, Lempicka continued to seek portrait commissions, but her style was out of date. After receiving some tepid reviews, she ceased to exhibit. She later lived in Houston, where her daughter lived, and finally settled in Mexico City, where she died in 1980.

Lempicka’s art, as with Art Deco in general, was out of fashion in the 1940’s and 1950’s, but a revival of interest in the style began in the 1960’s. A 1972 exhibition in Paris was well-received, and in America her work began to be acquired by a new generation of entertainers including (of course) Madonna. The art market quickly took note, and the rise in her prices has continued. Her painting of Marjorie Ferry, a British cabaret singer who performed in Paris in the 1930’s, was sold at Sotheby’s in New York in 2009 for $4,898,500. In 2020 the same painting sold at Christie’s in London for $21,155,780.

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait of Marjorie Ferry, 1932

Photo courtesy Askart.

A short film that accompanies the de Young exhibition includes an interview with Lempicka’s granddaughter, who as a child visited the artist during her last years in Mexico. Lempicka told her granddaughter that when she sold a painting in her heyday, she would buy a diamond bracelet. She said that she wanted to have bracelets “from here to there,” indicating the space between her wrist and elbow. That statement was more than the admission that she wanted more bling; it was the life philosophy of a tough cookie who knew that she had to look out for herself and acquire assets that were easily transportable if her situation changed and she had to leave town in a hurry.

Lempicka’s granddaughter said that the artist would have loved social media, saying, “She would have been a star on Instagram!”

Absolutely.