One of the joys and nuisances of having been trained as an art historian is that you constantly see life imitating art. I was attending the opening of The Armory Show two weeks when I was struck by the sight of a young woman tending bar. “Excuse me, but would you let me take your picture?” I asked her. “You remind me of a famous painting.” She graciously agreed to pose, and I took the photo below.

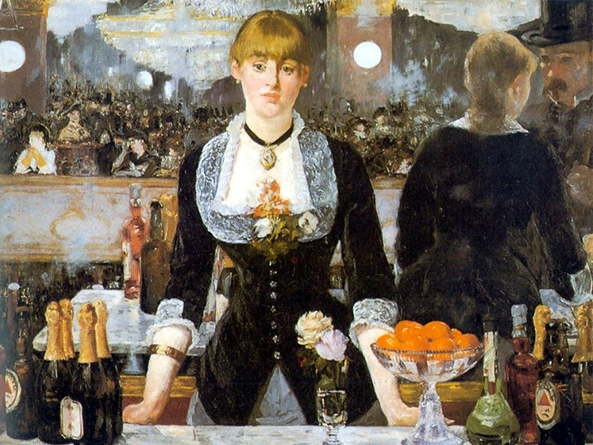

Some of you probably already know the painting I was thinking of, the Courtauld Gallery’s great Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

The Folies-Bergère was not yet the home of the Can-Can and the nearly-nude revue in 1882, when Manet painted his picture, but it was already a popular night spot that featured operettas, popular music, and gymnastics, not to mention copious amounts of alcohol. The similarities between the two images above made me think about the similarities between their two venues. Openings of art exhibitions have been popular social occasions for over 250 years, since at least the heydays of the French Salon and the Royal Academy, and the art always seems to have taken a back seat to the opportunity for the fashionable crowd to see and be seen.

Nevertheless, major art fair openings today have married glamour, fashion, and money in a way not seen since the hot nightclubs of the 1940’s and 50’s such as the Stork Club in Manhattan or the Brown Derby in Hollywood. Like those nightclubs, major art fair openings feature movie stars, tycoons, arm candy, and a well-established pecking order for who gets admitted first and who gains entry into the innermost VIP lounge.

But as far as art goes, forget about seriously viewing it at openings, whether at fairs, museums, or galleries. It’s like trying to view a painting in Grand Central Station at rush hour: you’re not going to be able to concentrate, and concentration is the subject I really want to discuss in this essay. Connoisseurship requires concentration.

Connoisseur – “a person who is especially competent to pass critical judgments in an art, particularly one of the fine arts, or in matters of taste: a connoisseur of modern art.” It is an article of faith among dealers of my generation that there is no connoisseurship anymore. “Young people!” we complain. “They’re all about Instagram, PDFs, and the visual equivalent of sound bites! How many of them have actually looked at an actual painting for more than a few seconds? How many of them would know a good painting if they saw it? How many could recognize a fake?”

I was ranting like this to my wife, and she pointed out that young people today are indeed interested in issues of quality, whether in matters of food, drink, or fashion. “They’re just not interested in the hundred-year-old art you and your colleagues sell,” she told me, irritatingly perceptive as usual.

So I stand corrected, but if you’re interested in art, whether it’s Hudson River School, American Modernism, or a painting done last week, to really appreciate it, you’ve got to take the time to look at it, and art fairs generally don’t have seats in quiet spaces where you can truly take in a work of art. Museums are wonderful, though they too often have a carnival atmosphere, especially if you’re in a special exhibition. But the guards won’t let you get close to the art, let alone allow you to take it off the wall to examine its condition and discover the history that you can tell from a look at the back of the painting. And do you know how much of the painting you’re looking at is even by the artist? Has there been major restoration done to the piece? I would suggest that the best way to develop your connoisseur’s eye is to spend a lot of time talking to dealers.

Museum curators have a great deal of knowledge, but they’re generally unavailable to the average museum goer. Dealers have knowledge, too, and while there are dealers who seem to make it a point of pride not to speak to hoi polloi, most of them are generous with their time. They would love to sell you a painting, of course, but there’s another reason: they’re suckers for the art they sell.

Dave Hickey, in the introduction to his great book of essays Air Guitar, spoke with gratitude of the dealers who taught him so much about art when he first arrived in New York, even though it was obvious from his outfit that he was in no position to buy something. “People would talk to you,” Hickey writes, “not because you were going to buy something, but because they loved the stuff they had to sell. The guy at the Billabong Surf Shop, I can assure you, wants to talk about his boards. Even if you want to buy one, right now, he still wants to talk about them, will talk you out into the street, you with the board under your arm, if he is a true child of the high water.”

When dealers joke about themselves as soulless salesmen or cynical manipulators of the market, they do so to hide an almost embarrassing truth: they love art. They love being around it, they love talking about it. I shouldn’t say “they,” I should say “we,” for I’m describing myself, too – I love looking at art and sharing my knowledge.

“Connoisseur” today has a faint odor of men with monocles examining a Ming vase, so perhaps we should put the term aside. Let’s just talk of people who know the good stuff when they see it. Such knowledge deepens their appreciation of art immeasurably. If you would like to be one of these people, I can help you develop your eye. Let’s talk.