Ellen Lanyon, a Chicago artist who later ended up in New York, often painted pictures that placed ordinary objects in dream-like juxtapositions with a decidedly spooky air. In an article on her work for Art in America twenty years ago, I wrote that I had always considered her to be your basic Corn Belt Surrealist, but that a fuller knowledge of her work had shown me she was much more than that. Ah, the danger of coining a phrase. When Ellen died four years ago, an obituary ignored the positive tone of my article, saying merely that a critic (sneeringly, it was implied) had once called her a Corn Belt Surrealist.

Looking back, I see that the problem was with the term Corn Belt — no one would object to an artist’s being called a Surrealist. In my New York provincialism, I was condescending to all artists not working in New York. There was also a lingering suspicion of artists working in a realistic style. When I was pursuing my graduate studies in art history, the history of modern art read like the book of Genesis – all those “begats.” Impressionism begat Neo-Impressionism, which begat Post-Impressionism and so on, all the way down to recent years, when Abstract Expressionism begat Post-Painterly Abstraction, which begat Minimalism, at which point painting was supposed to end.

The constant in the modernist version of art history was that art in the 20th century was tending inexorably toward abstraction and the flatness of the picture plane. Any artist who wasn’t in step with this progression was hopelessly retardataire, a dinosaur who hadn’t realized that it was supposed to be extinct. Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood were granted grudging inclusion in histories of American art – how could you ignore them? — but the praise tended to be back-handed, acknowledging them as cultural icons who were popular with the unsophisticated public.

The modernist paradigm turned out to have a limited shelf life, and realism came again into acceptance. A side effect of that acceptance was the revival of interest in artists from the first half of the 20th century who worked in a realist style, away from New York. That interest has kept growing, as evidenced by a show (or rather, two versions of a show) that I saw last fall at the Brandywine Museum in Chadds Ford, PA and last week at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta.

Rural Modern: American Art Beyond the City (the Brandywine Museum’s exhibition) and Cross Country: The Power of Place in American Art, 1915-1950 (the High Museum’s expanded version) contain art in varying realistic styles, produced across the country. The big names are there, of course – Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth, and others – but there are works by artists most people familiar with only the standard surveys of American art have never heard of. How about the Indiana artist John Rogers Cox (1915-1990), whose Wheat Field from around 1943 appears here (courtesy of The John and Susan Horseman Collection of American Art)?

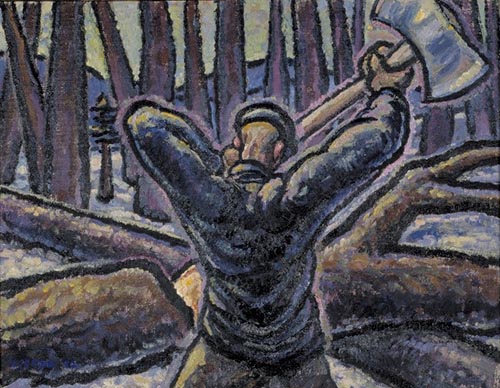

Or how about Harold Weston (1894-1972), who was among the first modernist artists to work extensively in the Adirondacks? His painting from 1922, The Lumberman (Private Collection), bears comparison with both American and European modernism of the time.

Or how about Roger Medearis (1920-2001), whose Godly Susan, 1941 (Smithsonian American Art Museum) bears the evident influence of his teacher Thomas Hart Benton but which has a sweetness among the tartness that I think Benton lacked?

None of these artists was a hick. They were all classically-trained painters who chose to work in an unfashionable style away from the New York art market. They paid the price for that choice. None achieved national fame in his lifetime; indeed, Medearis gave up painting for several years, unable to sell his works. (A dealer persuaded him to resume painting in his mid-40s.)

But they’re back, and the art market is paying attention: prices for major works by these artists have increased significantly in the past few years. Catch the High Museum’s show if you can (it’s up through May 7). And bear in mind the second of my two rules for collecting – better a great painting by a lesser-known artist than a mediocre painting by a famous one. Let’s talk about such artists. Call me.

Contact Me