Well, the 19th and 20th century American sales have come again and gone. Any new trends? Not really. Sotheby’s sale began with modernist paintings which initially sold well, with several works by Milton Avery exceeding their high estimates. Then things turned ominous. One of the stars of the sale, Edward Hopper’s Shakespeare at Dusk, failed to meet its $7,000,000 low estimate. After that, results were extremely uneven.

African-American works, continuing the trend of recent years, generally sold well, with works by Horace Pippen and Jacob Lawrence exceeding their high estimates. A large oil from the mid-1920’s by Hale Woodruff, Picking Cotton, sold for $764,000, more than tripling his previous auction record.

A first-rate gouache by Jacob Lawrence brought almost a million dollars, and a landscape with a church by Horace Pippin brought $300,000. The market for works by artists of color remains strong, as does the market for works by well-known illustrators – works by N.C. Wyeth, Norman Rockwell, and Joseph Christian Leyendecker all exceeded their estimates.

But Sotheby’s offerings by artists of the American West generally sold below their estimates, and buyers of works by the Hudson River School demanded that the paintings be of the Hudson River area, not scenes painted in Europe. The sale ended with a decided whimper, with 9 of the final 13 lots, all of them 19th century works, failing to sell.

Christie’s sale the following day was much more successful, with more desirable lots. Modernist art, again, was strong – Marsden Hartley, Charles Green Shaw, and Arthur Dove set records for work in their respective media. Works by figurative artists such as Joseph Hirsch and O. Louis Guglielmi, who were once dismissed as retardataire by critics in the age of Abstract Expressionism, also set auction records.

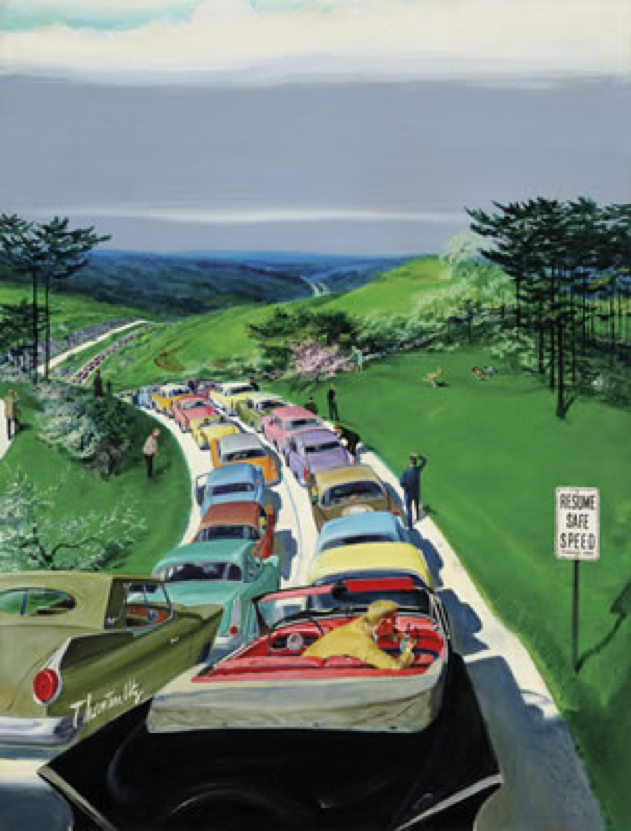

As for illustration art, ever hear of Thornton Utz (1914-1999), a commercial artist who did advertising illustrations for Coca Cola, General Electric, and the Ford Motor Company? Resume Safe Speed, a 1959 cover illustration he did for the Saturday Evening Post, had sold at auction for $89,630 in 2010. This time around, it sold for $137,500.

So the market for humorous, slice-of-American-life illustration is alive and well. While the demand for classic images from the period between the world wars remains strong, there is also an increasing demand for images from the Mad Men era, a time still bright in the memories of Baby Boomers.

Take another look at Picking Cotton above. It’s by Hale Aspacio Woodruff (1900-1980). Woodruff was born in Cairo, Illinois, in 1900 and grew up in Nashville, where he served as a cartoonist for the student newspaper of his segregated high school. After graduation, Woodruff moved to Indianapolis where he drew political cartoons for the Indianapolis Ledger, a newspaper serving the African-American community. He attended the John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis and later studied briefly at the Art Institute of Chicago and at the Fogg Art Museum School in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In 1927, aided by financial support from Edith Halpert, a New York gallery owner, Woodruff was able spend four years in Paris, where he studied with the noted African-American expatriate artist Henry Ossawa Tanner. He also met Alain Locke, who was a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Locke encouraged African-American artists to study the art of Africa, and Woodruff often accompanied Locke on visits to dealers and exhibits of African art in Paris.

With the coming of the Depression, Woodruff’s sources of patronage dried up, and he returned to the United States in 1931. He established the art department of Atlanta University, an historically African-American college. In 1936 he traveled to Mexico, where he studied with Diego Rivera, an experience that assisted him greatly in the execution of a mural on slave revolt commissioned by Talledega College, another African-American institution.

Woodruff was a supportive teacher of painting and printmaking, encouraging his students to depict what they saw, warts and all. This led to some critics to dub him and his followers “The Outhouse School,” as that humble building often appeared in the landscapes they painted.

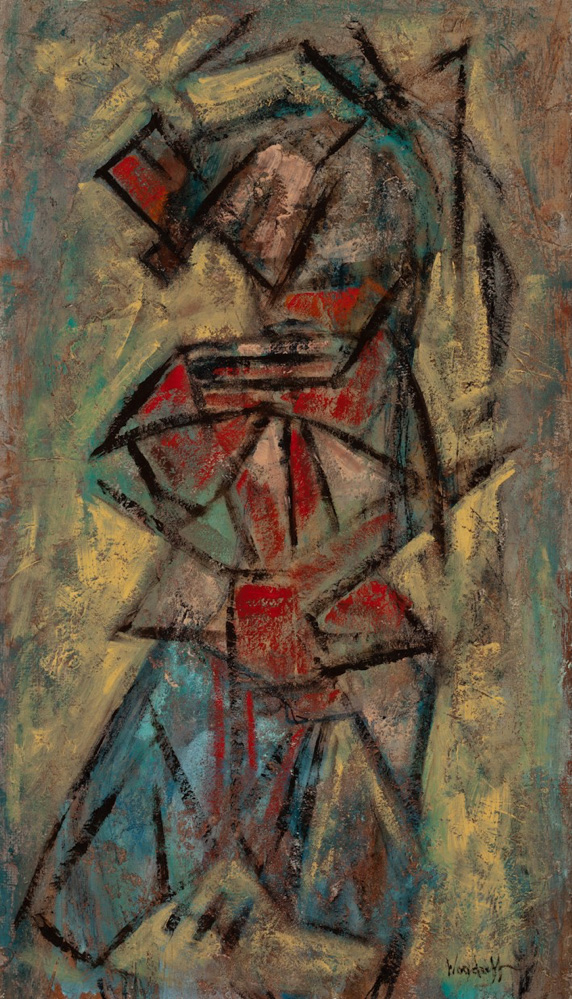

In 1943 Woodruff received a two-year grant to work in New York, and his residence in the city became permanent in 1946 when he accepted a position of the faculty of New York University. Abstract Expressionism was the dominant style when Woodruff settled in New York, and like many other figurative painters, he soon fell under its spell. An oil I currently have for sale reveals the influence of Abstract Expressionism, tempered by Cubist compositional technique.

The shift to an abstract style was not without controversy in the African-American artistic community. Woodruff was one of the founders of the Spiral Group, a New York-based African-American artists’ group that lasted from 1963 to 1965. While there was no common artistic style, the group was characterized by its experimental and eclectic approaches, including forms of modernist abstraction. A major point of contention among the group was whether artists should illustrate African-American experience in figurative art or if abstraction itself by African-American artists was a politically radical form of artistic practice. While short-lived, the Spiral Group ignited important debates about philosophy, creative integrity, and artistic freedoms among African-American artists — including the cultural community’s role in social change — during a time when few art critics were asking the same questions.

While the greatest collector demand for Woodruff’s work has been for his earlier Social Realist work, his abstract art has been steadily gaining in collector appreciation and has cracked the six-figure level at auction several times. My piece is much less than that. Let’s talk.