In 1981, in an act of faith that today makes me shudder at its innocence, my wife and I moved with our baby to New York from Chicago. The passage of time has mercifully dulled the troubles of those first days – moving into half the space we’d had in Chicago for twice the rent, looking for a job, closer to family, but cut off from our good friends back “home.”

Looking back, I am struck by the kindness and generosity of artist friends we had known in Chicago who had preceded us to New York. Michael Hurson and Ellen Lanyon invited us for dinner to their lofts almost as soon as we arrived and helped us deal with the inevitable culture shock at a time when we were struggling to find our feet.

One other artist with a Chicago connection reached out to us – George Deem. The connection was more tenuous but just as real – we had published a piece by him in White Walls, a magazine of writings by artists that we had founded five years earlier with our friend Buzz Spector. George invited us to his loft on West 18th Street, the same loft in which he would die 27 years later, where we met his partner, Ronald Vance. The supper that night was the first of many we were to have over the years, simple yet sophisticated, full of good food and lively talk, with the seemingly effortless attention to detail that marked our hosts as masters of entertaining.

The affection I feel for George and Ronald and those days surrounds me now as I try to write about George’s art.

George was born in 1932 in Decker, a small town in Southern Indiana, where his father was a cantaloupe farmer. He was a twin, but his brother died at age four, and George once told me about lifting the netting that had been placed over the open casket against flies at the wake to feel his dead brother’s face. A medium told George many years later that he had a presence circling him like a dark planet.

Growing up on a farm, helping his father in the fields, George was about as far from fine art as can be imagined, but he was struck by the art in saw in the Catholic church his family attended. For a while, he linked art and religion, and he spent some time in his teens at St. Meinrad near his home, a Benedictine archabbey where a cousin was a monk. His cousin, wisely recognizing George’s true vocation, told his parents that George needed to go to art school. So it was that George found his way to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His studies there were interrupted by two years’ service as a Military Policeman in Germany, and he used his leave time to travel throughout Europe, furthering the education of his eye that he had already begun in the galleries of the Art Institute.

After leaving the Army and finishing his art training, George moved to New York. Abstract Expressionism was winding down, but the gestural impulse that was at its base was encouraging younger artists to work in new ways. George had been inspired by Mark Tobey and admired the work of Bradley Walker Tomlin. As an oblate at St. Meinrad, he had studied calligraphy; now the calligraphic gesture became for him a sort of halfway point between the action painting and a more intimate, controlled manner of expression.

Small Paragraph, c. 1961-62, oil on canvas, 20 x 16 inches

The paintings were constructed by applying layers of paint and then incising calligraphic marks in a sgraffito manner. George did not sign the works in this series on their fronts, as he wanted none of the “words” to be legible, emphasizing the tension between gesture and language, between something we use or see every day and something mysterious.

But George was an artist with a deep sensitivity to the realist style, and it was inevitable that recognizable imagery would find its way into his paintings. A step that seems obvious in retrospect was to combine calligraphy resembling the handwriting that used to be found on snail mail envelopes with the postage stamps affixed to those envelopes.

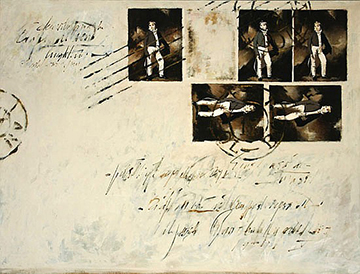

Cancelled Envelope (Raeburn), 1964, oil on canvas, 35 x 46 inches

The format allowed Deem to continue in his calligraphic style while inserting wry homages in the form of painted “stamps” to artists from previous centuries whom he admired, in this case, Henry Raeburn. Works such as this brought George critical comparisons to Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Larry Rivers who were using everyday commercial imagery to create art, and his work was included in exhibitions with those artists.

George was not a Pop artist, however; his sensibility was admiring rather than ironic, and his appropriation of imagery was more concerned with extending a tradition than with making a radical break with the past. Jan Vermeer was a particular touchstone for George. He made an intimate study of all of the Dutch artist’s works on exhibition in museums, and he painted over 150 works that make direct reference to Vermeer’s paintings.

But George roamed the length and breadth of art history, and he held an artistic dialog with artists from several centuries. Perhaps his greatest series of paintings was inspired by the use of the word “school” in art history, as in Hudson River School, or School of Tintoretto. George had the idea of taking the expression literally and painting what he imagined such schools must look like. His template for the series was Winslow Homer’s famous Country School, which reminded him of the schoolrooms of his youth, with their lift-top desks sporting inkwells. George populated such paintings with characters from his sources’ most famous paintings.

School of Mantegna, 1985, oil on canvas, 34 x 50 inches

Any of these paintings could serve as an illustration of Postmodernism. They appropriate, deconstruct, and reassemble art history. But they are not slapdash collages; the images are lovingly and painstakingly painted. And though often wry, they are not parodies; the old is placed in an unfamiliar context and made new.

I have written in earlier blogs about art historians’ need to place artists in predictable categories. Critics have never known quite what box to place George’s work in – Pop Art, Photorealism, Postmodernism, Figuration? And dealers have never known quite how to market his work as a part of some larger movement. But George’s work is strong enough to stand on its own, and as time diffuses the boundaries between hard-and-fast artistic territories, just where to place him will become less important, and his work will be admired for its very real merits.

By the way, I have the three works above currently in inventory. Call me.