It was the spring of 1985, and seven women artists were still pissed. The previous summer, the Museum of Modern Art in New York had held an exhibition entitled, “An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture” to inaugurate the museum’s newly renovated building. The exhibition had included the works of 165 artists, supposedly the best of the best. Only 13 were women. The women who met the following spring had participated in a picket line across the street from the museum during the exhibition’s run to protest the exclusion of female artists, but New Yorkers are fairly oblivious to picketers, at least if the protests aren’t accompanied by large, inflatable rats.

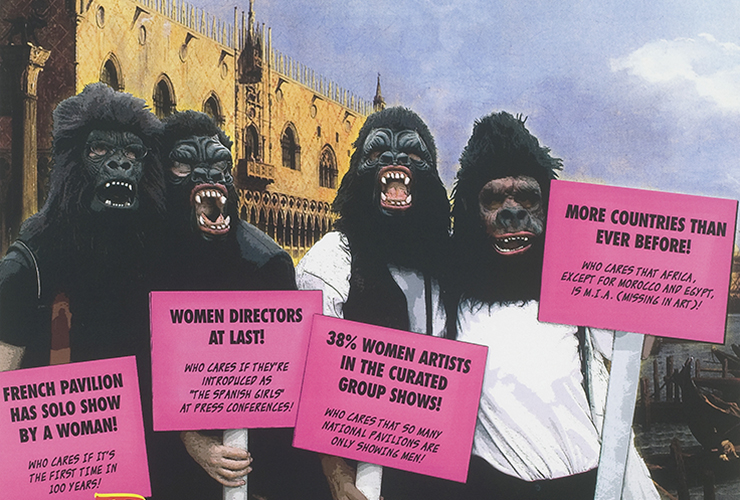

Something more media-savvy was needed. The seven women who met that spring decided to call attention to the facts and figures of the situation, laid out on inexpensive, well-designed posters, and many SoHo buildings soon had these posters pasted on their walls. But a moment foregrounded by nothing but grievance can turn off potential supporters, so the women brilliantly hit on another factor in their campaign: humor. In those days not long after the Vietnam war, Americans were well-acquainted with the term “guerilla warfare.” The women decided that the name of their insurrection against the art establishment would be the Guerilla Girls.

Photo courtesy National Museum of Women in the Arts

The founders of the movement and the other women artists who soon joined them wore gorilla masks in their public protests. To emphasize the collective nature of the movement, the identities of individual members were kept secret. As a spokesperson said, “We wanted the focus to be on the issues, not on our personalities or our own work.” Even the identities of spokespeople were kept secret; in addition to wearing their gorilla masks during news conferences, they adopted the names of famous deceased women artists. The secrecy of the group, which eventually grew to a high of about 30 members, was kept, adding an air of mystery to the protests. (There have been about 65 members over the years, with a handful still considered as members today.) A year after its founding, the Guerilla Girls broadened their cause to expose institutional racism, and women artists of color joined the movement.

I’ve sometimes wondered if Ellen Lanyon, an old friend who died in 2013 and about whom I have written in this blog, was among the founders of the Guerilla Girls. Born in 1926, she had certainly experienced her share of discrimination from artworld powers, and she was friends with many of the best-known female artists and feminist critics of the 1980s. But I never asked Ellen, and she didn’t volunteer the information.

Today, diversity and inclusion are the buzzwords for museums and other art institutions, so it might be assumed that the inequities highlighted by the Guerilla Girls almost 40 years ago are a thing of the past, but that is apparently not the case. According to Artnet News, a recent study of 350,000 works acquired by 31 American museums between 2008 and 2020 showed that works by women artists comprised only 11 percent of the acquisitions. For Black artists, the number was even worse: their works comprised only 2.2 percent of acquisitions and were included in only 6.3 percent of exhibitions.

In fairness to museums, it should be pointed out that many if not most of their acquisitions each year are donated, not purchased. If private collectors in the past century were unlikely to acquire artworks by women or persons of color, the pool of artworks available for donation to museums is going to be skewed toward works by white male artists. And no museum if offered a major painting by Claude Monet or Jackson Pollock is going to turn down the donation, explaining that they already have plenty of works by white males.

It is primarily by purchase of works of art by women and minorities that museums will be able to diversify their collections. As no museum in recorded history has ever complained about having too much money in its budget for acquisitions, the allocation of limited funds will need to prioritize the purchase of works by women and artists of color if injustices are to be rectified. Will such a policy lead to charges of reverse discrimination?

If just over 14 percent of the United States population self-identifies as Black, should 14 percent of all artworks purchased be by Black artists? Should a museum buying 50 works of contemporary art ensure that four of them are by Hispanic males and four by Hispanic females, as per current demographic data? What about gender and sexual preference? Should the artist’s being gay or transsexual factor into curators’ decisions? What about subject matter? If a museum has acquisition funds for only one Black artist, should it prioritize a realistic work that depicts Black life over an abstract work?

Here are two works done in the same decade by contemporary Black artists, the first by Sam Gilliam, a graduate of the University of Louisville who became a leading member of the Washington, D.C. group of artists who practiced what is now called the Color Field Painting. His artistic interests set him at odds with Black artists in the 1960s who advocated for art with a social message. He recalled Stokely Carmichael bringing him and several other Black artists together during this period to tell them, “You’re Black artists! I need you! But you won’t be able to make your pretty pictures anymore!” Gilliam, however, declined to change his style.

Sam Gilliam (1933-2022), Lady Day II, 1971,

Acrylic on canvas, 107 x 160 inches

Photo courtesy Christie’s

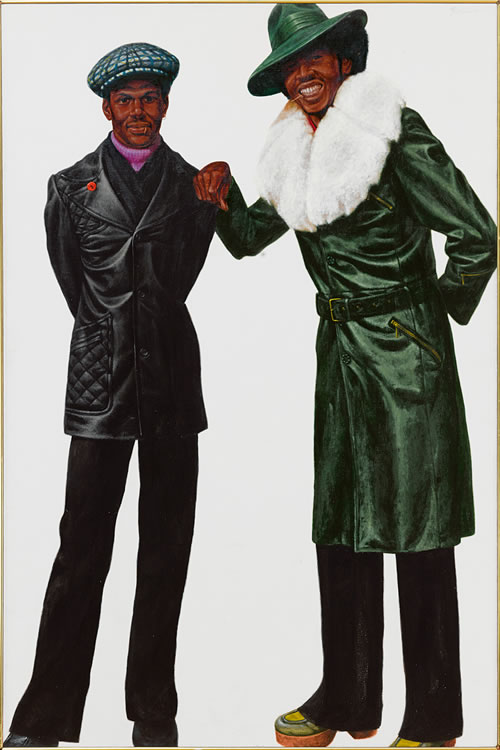

The second artist, Barkley Hendricks, attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and later Yale University. He taught art at Connecticut College until his retirement, but his most recognized paintings depict subjects drawn from Black neighborhoods.

Barkley Hendricks (1945-2017), Yocks, 1975

Oil and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 48 inches

Photo courtesy Sotheby’s

Both of these men were well-educated artists who had thought long and hard about the art they made. Is the art of one more representative of the Black experience than the art of the other? The market thinks so. The Sam Gilliam painting above sold at auction for $2,172,500 in 2018, a year after the Hendricks painting sold at auction for $942,500. But Hendricks’s market is now hotter than a two-dollar pistol. Yocks was resold for $3,740,00 in 2019. Four months ago, it was again sold, this time for $8,377,500. Collectors in the field evidently prefer recognizably Black subject matter over abstraction. Should museum curators likewise prioritize their purchasing?

Museum labels have commonly listed the artist’s name and dates in addition to their painting’s title. Will the labels in museums someday read something like, “Jane Doe, American, 1945-2018, white lesbian, Abstract #5”? How important is it for museum-goers to know the race, gender, and sexual orientation of the artist whose painting they’re viewing? (Of course, some artists might snap that their sexual orientations are nobody else’s damned business.) Can a viewer truly understand a work of art without knowing something of the artist’s background? A case could be made for such a statement.

Some may protest that any acquisitions program that prioritizes a particular group smacks of purchasing by quotas and goes against the idea that museums should exhibit only the best of the best. But what does that mean, and how is it to be determined? Criteria for judging the aesthetic value of works of art are always subjective. I’ll leave it to museum curators to decide how best to diversify their collections and how to determine that the paintings by one artist from a particular ethnic group are more desirable than those of another artist from the same group. Curators, feel free to email me with your suggestions.

Getting back to the founding of the Guerilla Girls — I called Andrew Ginzel, the son of Ellen Lanyon and a noted artist in his own right, and asked if he knew whether his mother had been a member. He didn’t know, he told me, though he mentioned her friendship with many feminist artists and critics, any of whose membership in the group would come as no surprise. But she had never discussed it with him.

From the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and the Yale Skull and Bones Club to the Guerilla Girls, secret societies have always held a fascination for those outside. True to the cause, Ellen took the secret to her grave.