The end to my days as an outsider artist occurred in the second grade. My classmates and I were making crayon drawings the way children do today – a strip of green along the bottom for the grass, with a child and a tree standing against the white of the paper, and a strip of blue along the top for the sky. Mrs. Goldwater, our teacher, told us to fill in the uncolored portion with blue. “The sky comes down to the horizon,” she told us. And we looked and saw that she was right, sort of. But our drawings were also right – we instinctively knew that when we were running around at recess it was not in a sea of blue as if we were underwater. It was clear where we were. The sky was Up There. From then on, however, we made our drawings with the sky coming all the way down to the grass. The days of untutored talent were over.

These reflections are occasioned by my having kept my New Year’s resolution: I attended the Outsider Art Fair in New York with my wife, to whom I give thanks for suggesting this blog’s title. I came away having seen a lot of interesting art, but with less clarity than ever about what the term “outsider art” means.

The term was coined in 1972 by Roger Cardinal as an English equivalent to the French term art brut (“raw art”) which was used by French artist Jean Dubuffet to categorize art made by untrained or mentally-ill persons. Such art has also been called “folk art” and “naïve art.” A term that is currently finding favor is “outlier art.” Dubuffet, who had dropped out of academic art training and was painting on the side while he worked as a wine merchant, found a raw emotional power in outsider art which he wanted to harness in his own art. This was nothing new, of course; modern artists since at least Gauguin had admired the vitality of folk art and had tried to encapsulate some of its techniques in the art they themselves made.

The problem I have with the term today is that it is applied, at least at the Outsider Art Fair, as a catch-all for any object whose maker never went to art school. I saw works at the fair ranging from a pair of beaded moccasins made by a Native American 140 years ago to highly accomplished work that would not raise an eyebrow if it were exhibited in a booth at Miami Basel. Given such disparity, the term as it is used at the Outsider Art Fair becomes almost meaningless.

What is “authentic” outsider art? I would leave the Native American moccasins out of the category. While their maker did not receive an MFA, she was undoubtedly trained in the aesthetics of beadwork by an older member of the tribe. She may have made her own variations in the work she did, but her accomplishment falls squarely within an accepted tradition. She was not an outsider in her own culture.

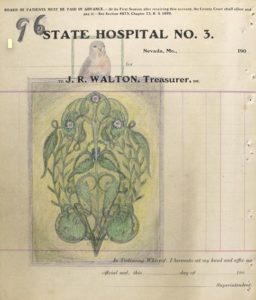

Three artists whose work I saw at the fair illustrate the difficulty of defining outsider art. The work of James Edward Deeds, Jr. (1908-1987) would certainly make the cut. Deeds spent 37 years in a Missouri mental institution, and many of his works were done on the institution’s stationery. His work often has the obsessive patterning than is a feature in the art of many people who are classed as mentally ill.

Likewise, Bill Traylor (1854-1947), who was born a slave in Alabama, worked as a fieldhand for much of his life, and did not start drawing until the age of 85, obviously counts as an outsider artist.

Traylor initially drew on cardboard or whatever scraps of paper he could find. Charles Shannon, a white artist, came upon Traylor drawing in the street, befriended him, and provided him with art materials. In 1940, Shannon arranged a gallery exhibition in Montgomery. Over the years, Traylor’s reputation has grown, and his work has become increasingly sought-after by collectors of outsider art. It has brought as much as $365,000 at auction.

But what about Mary Whitfield, born 1947 in Birmingham? She paints pictures of rural Southern life from an earlier era, with its joys (a mother playing with her child outside a rural shack), its work (African-Americans picking cotton in the fields), and its terrors (lynchings).

But Whitfield’s scenes of sharecroppers or lynchings are not something she witnessed. She is relying on stories and descriptions from her elders. And she is far from naïve – she has had a residency at the famous MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire and has received a grant from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Her work is sold for several thousand dollars in galleries and is in museum collections. She may be self-taught, but I have a hard time putting her in the same category as Bill Traylor.

It’s good, of course, that Whitfield is receiving good money for her art, as opposed to earlier outsider artists who received little or nothing for their works. Deeds and Traylor would have made their art, however, under any circumstances; they could no more resist the artistic impulse than a fish could refuse to swim. It is that unquenchable urge that attracts us still. All the rest is marketing. Such marketing can make the outsider art market a difficult sea to navigate. If you’re interested in making the voyage, I can help you. Let’s talk.