Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

-Thomas Gray

Years ago, I read an interview with the actor Bruno Kirby (Godfather II, City Slickers) who spoke in passing of the role that luck and connections had played in his career. “There are actors driving cabs,” Kirby said, “who could blow me off a stage.”

Kirby could have been speaking for any actor or artist. What if Michelangelo, instead of being raised in Florence, where he was trained by Ghirlandaio and soon gained the patronage of the Medici, had been raised in, say, Catanzaro and had been trained by the local stonemason there? It is possible that guidebooks to Calabria today would say something like, “In the Church of the Santissimo Rosario in Catanzaro can be found some amusingly vigorous carvings, now sadly deteriorated, by M. Buonarroti.”

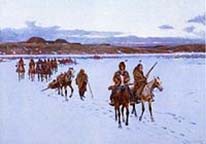

Talent and training are necessary for any successful artistic career, but luck and location play significant roles as well. I think that most connoisseurs today would say that the three greatest late 19th – early 20th century artists to paint the American West and its cowboys and Native Americans were Frederic Remington, Charles Marion Russell, and Henry Farny. Farny was by far the best-trained of the three, having studied at the Dusseldorf Academy. Travels in the West, combined with a solid academic foundation, enabled Farny to paint pictures like Departure for the Buffalo Hunt, below:

Yet only 40 years ago, Farny was practically unknown outside of Cincinnati, his hometown. The reason is that he returned to Cincinnati after his studies in Europe and worked there the rest of his life. National careers are made in New York. Remington lived in New Rochelle, just outside New York City, with easy access to galleries and publishers. Russell, though he lived in Great Falls, Montana, was dragged to New York every few years by his wife, who was a formidable dealer. She would set up shop in a hotel suite and make sure Russell’s works were seen by the right people. Farny was always well-known in Cincinnati, but it was not until the publication of a monograph on him in 1978 that his work was brought to national attention. Only in recent years have the prices for his work finally begun to approach something like parity with those of the other two great Western artists.

It is still difficult for an artist who hasn’t spent at least some time in New York to earn a national reputation. In addition to important galleries and major art fairs, the art press and the art critics with a national following are concentrated in New York. Exposure and critical championing are the things on which fame is built.

Consider the following painting, Tragic Landscape, which I have for sale at present.

The artist is Guy Johnson, born in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1927. He established a college teaching career, had his first one-person New York show in 1955, and was able to quit teaching in 1967 to devote himself to painting. His work gained attention as a part of the Photorealist movement (though his art had a decidedly Surrealist bent). He was reviewed in national publications, and he seemed to be headed for the big time. But you probably haven’t heard of him, because he met a wealthy Swedish dealer who loved his work and offered to purchase his all of his future output.

It sounds like a sweet deal. What artist wouldn’t want a steady paycheck just for painting, no teaching responsibilities attached? Johnson took the offer and moved to Europe, living in Copenhagen and finally settling in Amsterdam. But the move hurt his career in the long run. American art critics lost sight of him, while to their European counterparts he was neither fish nor flesh, an American but not quite. What pigeonhole could he be put into? Art historians and critics love pigeonholes, straitjackets though those may be for living artists.

Artists can miss chances in many ways. Some, like Jan Matulka and Richard Pousette-Dart, seemed to have an absolute genius for shooting themselves in the foot when it came to dealing with critics or curators. But many fine artists were simply in the wrong place, physically or stylistically, during their careers and had to be content with minor recognition.

“Listen,” I tell my artist friends, “In heaven there’s a gallery where works of art are hung strictly by aesthetic merit. On those golden walls, right next to the paintings of Raphael, are the paintings of Mrs. Gertrude MacGonagall of Frostbite Falls, Minnesota, who painted only for her children and whose works were all destroyed in the barn fire of 1887. But that’s in heaven. On earth, fame is a lottery. You’ve got your ticket. Good luck.”