In 1978, Roberta and I joined our friend Buzz Spector to found White Walls: A Magazine of Writings by Artists. One of the few publications dealing with word-and-image art, it soon began to attract submissions by some notable artists in the field. One evening as we sat around a table examining submissions for the second issue, Roberta held up a submission. “We’ve got to publish this,” she said in a tone that brooked no dissent. Not that there was any dissent, as Buzz and I were likewise struck by “Spell,” our introduction to the work of Rosemary Mayer.

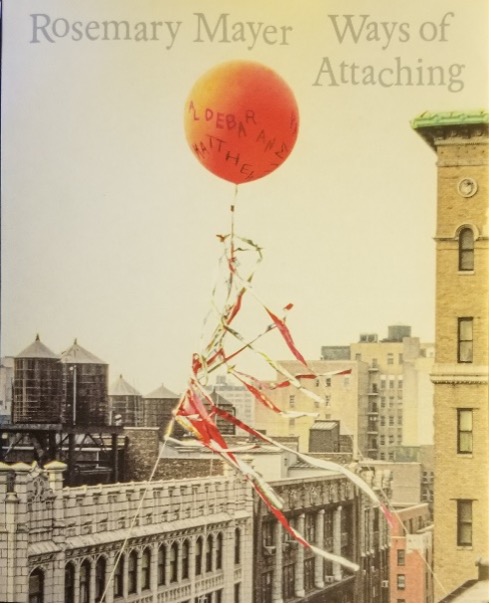

I have been thinking recently about Rosemary, who died in 2014, because she’s been having quite the posthumous career lately. In the past couple of years, exhibitions of her work have been held in New York, Germany, and England. A recent visit to the gift shop of MoMA P.S. 1, the Long Island City venue of the Museum of Modern Art, revealed two books by or about her on sale. I recently received Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, a handsome new monograph on her life and works.

Monograph cover.

Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter und Franz Konig.

No artist achieves a posthumous career without champions, in this case Mayer’s niece, the art historian Marie Warsh, and Mayer’s nephew Max Warsh. What they have been able to do for their aunt is all the more remarkable because of the ephemerality of Mayer’s art.

Born in 1943 in Ridgewood, then part of Brooklyn (it is now part of Queens, go figure), Mayer majored in Classics at the University of Iowa, but on her return to New York began art studies at the Brooklyn Museum Art School and later in Manhattan at the School of Visual Art. By 1971 she was exhibiting sculpture made of fabric at group shows and was writing exhibition reviews for Arts Magazine. A major boost to her career occurred the following year, when she joined with other artists to found A.I.R (Artists in Residence) Gallery, the first cooperative gallery run by and for women.

Made of things such as fabric, paper, sticks, and balloons (and, in at least one case, snow), many of Mayer’s works were by their very nature temporary, surviving today only in documentary photos, and hinted at by annotated preparatory drawings. A major influence on her aesthetic was the Florentine Mannerist painter Jacopo da Pontormo, who shared her love of gorgeously-tinted, draped and folded cloth.

Rosemary Mayer, Galla Placida, 1973, satin, rayon, nylon, cheesecloth, nylon netting, ribbons, and wood, with dyesand acrylic paint. 108 x 120 x 60 inches.

Photo courtesy Rosemary Mayer Estate.

Mayer’s work attracted favorable critical attention, but ephemeral works of art do not attract many collectors, and Mayer had to cobble together a living from teaching gigs, temp work, occasional sales, and the like. She lived very frugally in a fifth-floor loft in Tribeca, which was at that time not at all the high-fashion neighborhood it is today. There was no doorman and no elevator in her building. In those days before cell phones, if you wanted to make a visit, it was necessary to call her from the phone booth on the corner. She would then climb out her window onto the fire escape and drop the building key wrapped in a pair of socks. Retrieving the key, you could unlock the door and begin the climb up those seemingly endless stairs.

Another rent-paying gig was as artist’s model. “When I need money,” she told me once, “I call Raphael Soyer and say, ‘Raffi, I need to pose’.” In the years since her death, I have occasionally rounded a corner at a museum or auction exhibition to encounter her, clothed or nude, in one of his paintings, and I always give a posthumous greeting.

Raphael Soyer, Rosemary in Thought, 1975. Oil on canvas, 34 x 26 inches.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Henry Ward Ranger

through the National Academy of Design, 1999.77.

Mayer had her champions, but her uncompromising nature in art too often bled over into daily life. She could be prickly, and she did not suffer fools gladly. But the work remains and is surprisingly durable, an idea which assumes physical shape from time to time by means of present-day helpers.

The Estate of Rosemary Mayer installing her sculpture Portae (1974), for the exhibition “Future Variations,” at Soft Network, 2022.

Photo by Sara VanDerBeek.

Wood splits, paint cracks, paper yellows, and canvas becomes brittle. Yet the impulse to beauty, however the artist defines that maddening term, can cling to those objects at least for the artist’s lifetime and sometimes beyond it. Sleep well, Rosemary. Your work is still alive.