Any art dealer knows that the size of the painting he or she is offering is going to be an important factor in getting a collector to purchase the artwork. Collectors with loft-style walls may make exceptions for large contemporary paintings, but dealers in older art encounter real resistance when offering a painting larger than, say, 30 x 40 inches. Collectors protest that they just don’t have the wall space.

This collector resistance is a factor in appraising as well, a point brought home by two recent occurrences. The first was a tour of Radio City Music Hall with a group from the Appraisers Association of America. The men’s and women’s lounges of the building are decorated with some impressive artwork, none more impressive than the 1932 Stuart Davis painting entitled “Men Without Women” in the downstairs men’s lounge.

It’s a huge and lovely work, almost 11 by 17 feet in size. As appraisers, my colleagues and I couldn’t help asking ourselves, “What’s it worth?” We knew that important Davis paintings have brought real money at auction – twelve of them have sold for over a million dollars each, and the record price, $6,847,200, was set only a year ago. But what is the Radio City painting worth?

On the plus side, it’s instantly recognizable as a Stuart Davis painting, an attractive composition with large, simplified forms – pipes, cards, gas pumps, barber poles, and the like – juxtaposed with each other. On the other hand, the palette does not have the vibrant reds, blues, yellows, and greens that characterize his most popular paintings. Perhaps Davis was constrained by the need to fit into a larger decorating scheme.

And then there’s the size. How many private collectors could accommodate a work this large? The primary market would have to be the few major museums that have the deep pockets to purchase a painting of this importance. Given the limited clientele for such a work, my colleagues and I came up with a rough valuation of $10 to 15 million, assuming the work is in good condition. That’s only about twice the value brought by a painting only four percent as large. Size does matter.

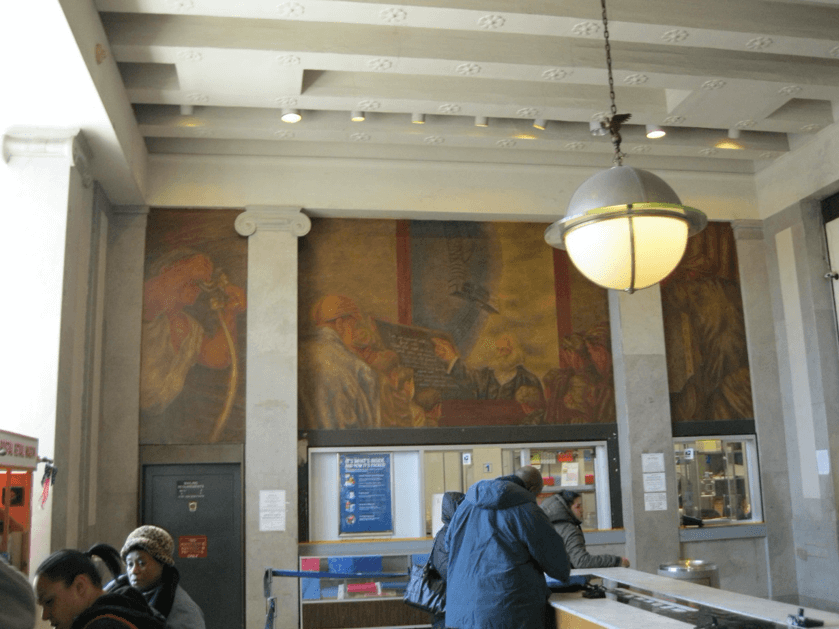

On the other hand, the Davis painting is oil on canvas, meaning that it can be removed from its location and sold if the owner so desires. What about some paintings I have just appraised which are part of the wall on which they appear? Six years after Stuart Davis completed the painting above, the artist Ben Shahn was commissioned to paint thirteen murals for the lobby of the Bronx Central Annex Post Office Building. The works, done under one of several government programs which today we generally lump under the shorthand category WPA (Works Progress Administration), were a part of the effort by the U.S. government to provide employment for workers (in this case, artists) suffering from the effects of the Depression. Shahn painted these works with his partner, Bernarda Bryson. Here’s an example of what three of the murals, taken when the station was in operation.

The murals were executed using the fresco method, in which the paint is applied to wet plaster. The paint soaks into and bonds with the plaster as the plaster dries. It becomes literally part of the wall. Removing such a mural would require the enormously time-consuming method of stabilizing the front of the painting with a support and then grinding away the wall behind the painting to reach the layer of plaster, generally less than an inch thick, on which the mural is painted. The mural is then affixed to a new support. As you can guess, it’s an immensely expensive procedure – a 14-by-47-foot fresco by Peter Hurd was removed from its wall a few years ago and reinstalled elsewhere at a cost of half a million dollars. The smallest of the Shahn/Bryson murals are 9 by 3 feet. The largest ones are 12 by 17 feet. I cannot begin to imagine what a contractor would charge for the removal of all thirteen works.

Like many old post office buildings, the Bronx Central Annex building has been sold, as the Postal Service wants more modern facilities. The buildings are sold, however, with the proviso that the U.S. government (in this case, the GSA) retains ownership of the WPA artwork. The new building owner is required to provide insurance for the artwork. That was where I came in.

I was retained to appraise the Shahn/Bryson murals to ascertain a Retail Replacement Value for insurance purposes. All of the calculations that my colleagues and I went through with the Stuart Davis mural were applicable here. Ben Shahn is an important artist, and his works from the 1930s and 1940s are in particular demand. Two tiny mural studies from this period, each less than 6 by 16 inches, brought $200,000 each at auction a year ago.

So on the plus side, the Bronx murals are from his most sought-after period, and their subject – laboring men and women – is exactly what collectors of Social Realist art want. But you can’t move the murals without enormous expense, and 70-plus years of being exposed to the vicissitudes of a public space have led to some condition issues. I had to juggle all of those elements in coming up with an insurance value. Client confidentiality prohibits me from revealing the assessed value, but let’s simply say that it was a lot more than the tiny Shahn mural studies brought at auction and a lot less than the Stuart Davis painting would bring if you removed it from Radio City and sold it.

Like the objects it assesses, appraising is an art, not a science. Much of the writing that goes into an appraisal involves explaining why I set the value I did and constructing a case that will stand up in front of scrutiny by the IRS and other parties. I’d be glad to help you. Let’s talk.