In 1981 I arrived in New York, jobless and with a wife and a baby daughter to support. I had worked in art publishing in Chicago and hoped to find something similar in New York, but a professor I had known at the University of Chicago called me and made a suggestion that changed my life forever: he advised me to go see a dealer he knew, Ira Spanierman.

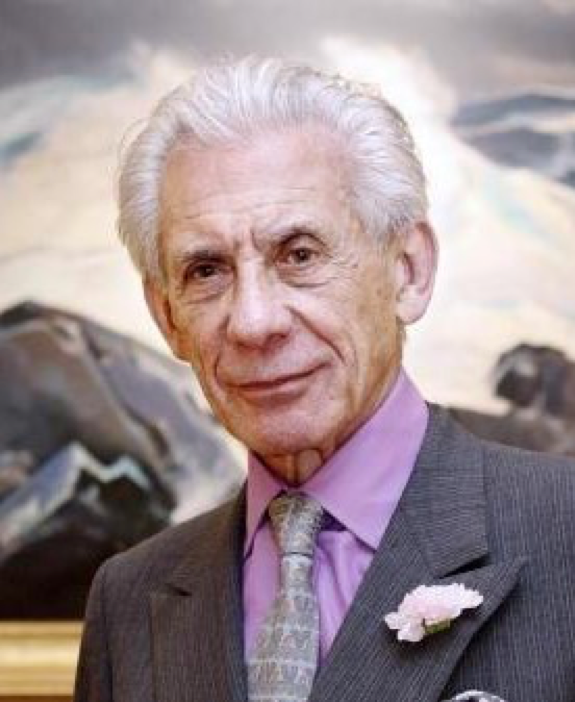

A day or two later, I was sitting in front of a desk in the gallery, being interviewed by a 53-year-old man who did not match my preconceptions of what a Madison Avenue dealer should look like: he had collar-length hair, a Fu Manchu mustache, and a soul patch under his lower lip. He was wearing blue jeans and a denim shirt unbuttoned to his sternum. I was seeing the last vestiges of sartorial rebellion. Ira had always fluctuated between hip and Saville Row, but shortly after I went to work as his new second banana, he shaved the patch, trimmed his mustache, shortened his hair, and settled into a routine of elegant bespoke suits.

I had, all unknowingly, enlisted in what I came to call “the boot camp of the art world.” Ira was extremely demanding – over the course of my four years with him, I saw people last from one day to six months – but if you could cut it, you got a lot of responsibility very fast. A week after joining him, I was juggling phones, wheeling and dealing, and giving a creditable imitation of an experienced art dealer.

Ira had dealt in all kinds of art since his youth. His father owned Savoy Art and Auction Galleries, one of several small auction houses at that time in New York that held weekly sales of all kinds of household goods – paintings, rugs, silver, china, you name it. I asked Ira once why he hadn’t continued in the auction business. “We had to just grind the material out, because there was going to be another sale in a week,” he told me. “I sold a lot of things that I thought, if I only had time to work with it, I could get a lot more money.” His father was what might be described as difficult. We once had an elderly couple in the gallery who had been clients at Savoy. “Yes,” said the husband, reminiscing about the old days, “I always remember your father, standing in the balcony and screaming, “IRA! WHERE ARE YOU?”

Ira got his temper from his father. Over the years, my semi-affectionate nickname for him, The Iratollah, has brought knowing laughs from other Spanierman alumni. The ones who were there long before I came had tales far hairier than mine. I don’t know that I wholly believed the former employee who swore that he had seen Ira break an oil on panel over the head of a restorer who had botched a job, but I wouldn’t bet big money against the notion, either. Ira’s rages could be epic, though by the time I worked for him, their physical manifestations generally peaked at kicking furniture and screaming.

But the wild-man days – the stories of Ira in the 1960’s, wearing a cape and taking a limo from one party to the next, were the stuff of legend. He was handsome and magnetic (“He looked like a young Jack Jones,” his sister assured me) and moved in a variety of circles. Marriage didn’t seem to slow things down much. His son Jon told me of wandering into the living room one night as a boy to find a party going on with the cast of Hair standing around naked, smoking joints. But Ira had the self-awareness to realize that continuing that lifestyle would kill him, and I always gave him credit for having the self-discipline to give up alcohol and whatever other substances he might have been using. When I worked for him, he didn’t drink at all.

People who give up alcohol, however, can transfer obsessive personalities to other fields, and Ira was a world-class control freak. Many a time after a brief subway delay, I emerged from the 6 Train at 77th Street and sprinted the three blocks to the gallery, knowing that Ira had already called my wife, demanding to know where I was. I was sure to hear about being two minutes late, though Ira had no problem keeping me there after closing time. I was lucky that there were no cell phones back then. A standard occurrence when checking into a hotel while traveling on business was a message waiting at the front desk, instructing me to call Mr. Spanierman at once. Hotel breakfasts on the road were liable to be interrupted by bellhops proclaiming, “Call for Mr. Upshaw!”

In those days, my family spent our two-week vacation at a little town on the Connecticut Sound. The house we rented had no phone. “But how will I be able to reach you?” Ira asked. “You won’t,” I assured him. During the day, small planes would cruise over the Sound’s beaches, towing signs that bore messages like “Fish Fry Tonight – Madison VFW.” Roberta said, “I wonder when we’ll see one that says, ‘Reagan – Call the Office’.” She was only half-kidding.

But Ira’s craziness could be leavened by humor. He was once in my office, yelling at me for having screwed something up. “How could you let that happen?” he demanded angrily. I had been having a bad day even before our run-in, and I slammed my fist on my desk. “BECAUSE I’M AN IDIOT, IRA!” I yelled back, “OKAY?” He stormed out, but when I saw him a few minutes later, he said impishly, “I don’t like to hear you running yourself down like that. ‘Occasional moron’ would suffice.”

I spent four years working for Ira before I burned out. I finally left when I grew tired of talking out loud to myself on the subway. But I covered a few auctions for him after I left the gallery, and we stayed friendly. Sharing a cab back from a reception at the Brooklyn Museum a few years after I had left, I complimented him on the strong staff he had put together at his new gallery space. “You’ve got Betty, you’ve got Debbie, and Gavin, and Ellery – the Four Horsemen.” “Yes,” he laughed, “And me – the Apocalypse!”

These reminiscences are occasioned by the fact that Ira died a couple of weeks ago. At the memorial service, the featured speakers talked of Ira’s support of catalogues raisonnés and other scholarship. Those of us who were alumni, however, spoke among ourselves of getting another kind of learning from him. In that spirit, here are some things that Ira taught me.

General rules: Portraits are hard to sell. Oval paintings are hard to sell. Still life paintings with oranges in them always sell.

Quality, not quantity: “It costs you as much to frame a $1,000 painting as it does a $100,000 painting,” Ira told me. “It costs you as much to photograph it, to store it, and to ship it out on approval. And you have to work just as hard to sell it.” Given all the incidental costs, he was saying, you’re better off with one $100,000 painting than one hundred $1,000 paintings. Yet Ira loved to buy paintings. He said, “I used to go to Christie’s East or PB84 sales (an old Sotheby’s venue) and buy 25 paintings that I found something of merit in. And then five years later, I still have 20 of those paintings.” One of the jobs he gave me, therefore, was to talk him out of buying lesser works and concentrate on the big things.

Don’t ask what you can buy it for, ask what you can sell it for: In those days, dealers owned a large percentage of their paintings, unlike today, when most works are consigned. Calculate what you can sell the painting for, Ira taught me, and then make your offer to the owner a percentage of the price you are confident you can get. Ira was once talking with a dealer who had a chance to buy an important Theodore Robinson painting and wanted Ira to do a joint venture with him. “What do you think we can ask for it, Ira?” he asked. “Well,” Ira replied, “That depends. If we buy it for $250,000, we’ll ask $350,000. If we can buy it for $150,000, we’ll ask $500,000.” It sounds paradoxical, but it wasn’t. Ira was saying that if you get into a painting at a low figure, you can afford to put a hefty tag on it and wait for your price. Ira was never afraid to wait.

Human nature: Ira understood what designers of lingerie have always known – it’s not what you can see, it’s what you have to imagine. We once acquired a small Edward Henry Potthast beach scene whose surface was brown from years of cigarette smoke. Ira put a little acetone on a Q-Tip and cleaned a dime-sized spot, turning a muddy brown into the sparkling white crest of a wave. A big collector was coming in the next day, and Ira intended to show the Potthast to him. “What do you think, Ira?” I asked. “Want me to run it down to Joel Zakow and offer him a bonus if he can clean it by tomorrow?” Ira knew that the collector coming in was sophisticated enough to imagine how nicely the painting would clean up. “No, leave it alone,” he replied. “It’ll never look better than it does right now.”

More human nature: There was an out-of-town dealer who was notorious for stiffing creditors, but we sold him a lot of art. Ira was careful, however — we filed UCC forms retaining title to the paintings until payment in full was made. The dealer had to give us post-dated checks (he always wanted a pay-out) and it was made clear that he should not even think about calling the gallery a day or so before the next instalment was due and asking if we would hold the check for another week. The checks would be deposited on schedule. “It’s simple,” Ira told me. “If you give X a chance, he’ll screw you. And then he’ll be unable to come back, because he screwed you. But if you don’t let him screw you, he can always come back to do more business. If you keep him on a very short leash, you’ll keep him as a customer.”

Never miss a chance to sell: For much of my tenure with Ira, one of the most important collectors of American art was Baron Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza. Ira would miss no opportunity to meet with “Heinie,” as he called him, and if Mohammed couldn’t go to the mountain, then the mountain would come to Mohammed. A couple of years after I left Ira, I was reading an interview with Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza. The interviewer had come to meet the Baron at his suite in the Pierre Hotel, but the interview was a half hour late in getting started. When the interviewer was finally ushered in, the Baron apologized for the delay, saying, “The American dealer Mr. Spanierman was here. He had asked to see me for just a minute to show me some photographs of paintings. When I expressed possible interest in one of the pieces, he happened to have it in a car downstairs.” I laughed out loud when I read the story – it was classic Ira.

Location, location, location: When Ira left his 78th Street location, he moved twenty blocks south. When I first heard of the move, I thought he was moving to the Fuller Building on 57th Street, the site of several galleries. But Ira had moved to 58th Street. The luxury Four Seasons Hotel had just been built next door to the Fuller Building. Both buildings had main entrances on fashionable 57th Street. Limousines, however, were not allowed to double park on 57th Street while waiting for their clients; they had to wait by the rear entrance on 58th Street. Ira had picked his new gallery location, he told me, knowing that any guest at the Four Seasons with a limousine was going to come out of the hotel’s back door, directly across the street from a gallery whose display windows would be filled with colorful paintings. It was a brilliant piece of marketing. When I joined Ira, I had had a graduate school education in art history, or “History of Slides,” as we jokingly called it. Speaking with Ira’s alumni over the years, I have heard over and over about how their real education in art came from learning from him how to look at, interpret, and physically examine a painting, including its stretcher and frame. I have written elsewhere about how Ira taught me to appreciate works that were not conventionally attractive. The education was worth the craziness.

When I heard Ira was closing his gallery and retiring, I sent him a note, wishing him well in this new phase of his life and thanking him for all he had taught me. The remaining inventory was interspersed with the offerings of several auctions at William Doyle Galleries. Going through the previews for those auctions, Roberta and I kept noticing how many times a small painting called to us from among the dozens of the artworks on the walls. Drawing near for a closer inspection, we would read a label informing us of the painting’s provenance – Spanierman Gallery. His eye was superb.

There was something I for which I forgot to thank Ira in my farewell note – when my daughter was two, Ira gave her a stuffed dog for Christmas, a dog she promptly christened Waldo and which she has kept to this day. I have worked for other dealers, but none of them ever gave my daughter a gift.

In a recent email to me, a Spanierman alumna summed him up: “A complex person, capable of great kindness and awfulness, but certainly one the world’s great, large personalities and like no one else. Definitely the end of an era. I learned more from him than anyone else.”

Kindness, awfulness, and an eye. What an eye.