Roberta and I were in Western New York a few days ago and took the opportunity to view the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum at Alfred University, a school which a friend who is a ceramic artist calls, “the established Mount Olympus in ceramic education in America.” It’s well worth a visit if you’re out that way.

Susan Kowalczyk, the curator of collections, graciously gave a us a tour of the museum’s storage area whose shelves contained one treasure after another. Going through the objects, I saw a couple of works that took me back in time – ceramic pieces by Ruth Duckworth. I had met Ruth on several occasions when I was a graduate student in art history at the University of Chicago. She was only in her mid-50’s at the time, but she was considered by many of her colleagues in the studio art department there to be a dinosaur.

Born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1919 to a Jewish father and a Lutheran mother, Ruth (née Windmuller) was 14 when Hitler came to power. Realizing the danger Jews were in, her family arranged for her to emigrate to England at the age of 17, where she joined a sister in Liverpool. She already knew that she wanted to be an artist, so she applied to the Liverpool School of Art. When asked in her interview what kind of art she wanted to make – painting, drawing, or sculpture – Duckworth said she wanted to do all three. The director protested that she couldn’t do both painting and sculpture, but Duckworth blithely pointed out that Michelangelo had done so.

She worked as a puppeteer and later in a munitions factory in England during World War II. After the war, she studied sculpture, supporting herself by carving tombstones for three years. “When I noticed that my own carvings were developing curly edges like roses and ivy leaves,“ she said later, “I felt it was time to quit.”

She married British artist and designer Aidron Duckworth in 1948 and continued to work as a sculptor. By the mid-1950’s she was focusing on clay as her chosen medium. Sharing a studio with her husband, who was designing fiberglass chairs, she spent half her time producing tableware and half producing industrial pieces. She found herself drawn to porcelain, later calling it, “a very temperamental material. I’m constantly fighting it. It wants to lie down, you want it to stand up. I have to make it do what it doesn’t want to do. But there’s no other material that so effectively communicates both fragility and strength.”

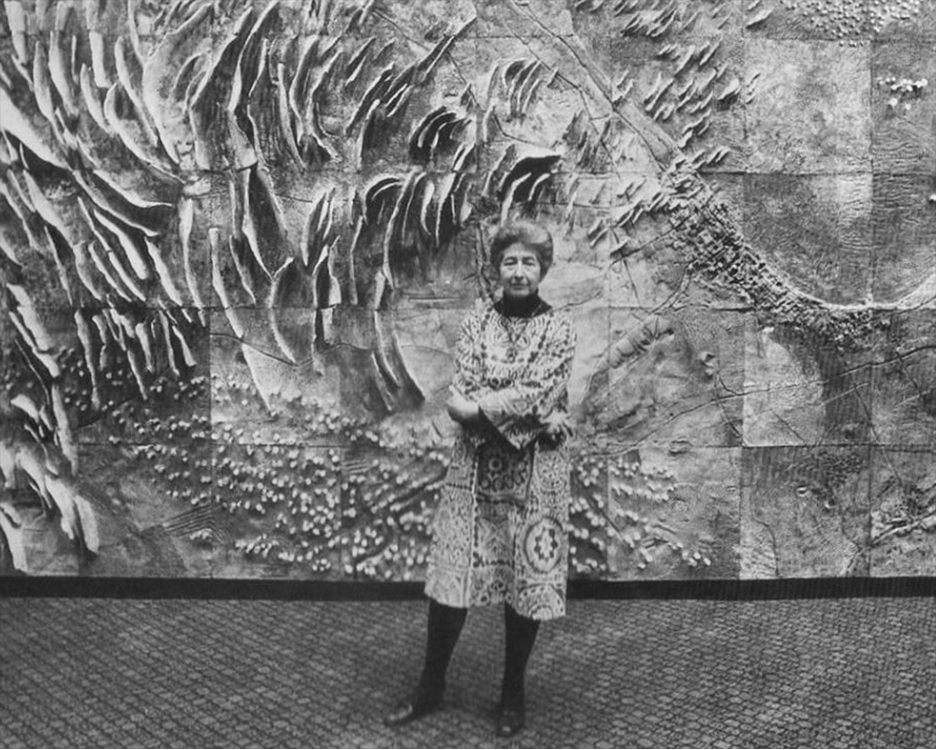

Duckworth had made a name for herself when the Craft Center of Great Britain recommended her to The University of Chicago in 1964. Intending to teach there for only a year, she began to receive commissions for installations such as “Earth, Water, Sky” at the university’s Geophysical Sciences Building, and she ended up living in Chicago for the rest of her life.

For all of her commercial success (or perhaps because of that success), however, Duckworth was treated with barely-disguised condescension by many of her colleagues in the studio art department. It was the heyday of Minimalism and Conceptual Art. Painting itself was looked at as a retardataire medium; who was this woman (another strike against her) working in clay? Clay is for making things like teapots, lady. We’re Serious Artists here!

In 1977 Duckworth decided to leave, partly in order to save her strength for large projects, but also because, as she wrote, “I feel saddened by the lack of appreciation for creativity and for the practice of Fine Art that is now the University’s attitude.” She moved to a space in a former pickle factory on Chicago’s North Side and continued to work at her art until her death in 2009 at the age of 90.

Well, Duckworth may have been a dinosaur, but if so, she was a T-Rex. The climate for art such as hers has changed substantially since those days. Feminist art theory began to pay serious attention to art made in media previously considered suitable only for women’s craftwork – clay, embroidery, and fabric. The boundary between “high” and “low” art had already been partially erased by Pop artists, but 1960’s counterculture interest in Buddhism and other Asian religions also contributed to a re-evaluation of the Western distinction between art and craft, as Asian aesthetics made no such distinction.

Duckworth has definitely had the last laugh. Her works have been collected by major museums, and retrospective exhibitions have been organized by both American and European museums. Her pieces have sold for more than $36,000 at auction since her death. Her former colleagues, on the other hand, have largely been forgotten, with their works selling for a few hundred to a couple of thousand dollars at auction on the rare occasions when they are offered.

Artistic theories come and go. What keeps a work alive is beauty, maddeningly difficult as that term is to pin down. And Duckworth’s work is beautiful. Roberta and I managed to scrape together the money to buy one of her pieces when we lived in Chicago, aided by a kind dealer who allowed us to pay it off over time. On the day that we picked it up from the gallery, we were having dinner at the home of Marvin and Mary Sokolow. Marvin was a dealer in Asian art, and when he learned that we had just purchased a contemporary ceramic piece, he scoffed, wondering why we would waste money on such a thing, when for a little more we could have bought an antique work. He asked to see it.

I unwrapped the Duckworth bowl and put it in front of Marvin, who looked at it for a long time. “Shit,” he said finally, “It’s really good.”