I was once visiting a collector’s home, admiring his works of art. The paintings were first-rate and had one thing in common: they were all nudes. Even the paintings which would properly be classed as landscapes had nude ladies populating them.

I asked him what the focus on nudes was about. “It’s easy,” he said. “I learned long ago that if you collect nudes, you get the field to yourself. Corporations won’t touch them. Museums are afraid that they’ll get angry letters from members. Some collectors have young children, and they’re not comfortable having nudes around. I’ve got important paintings by major artists that I bought for a fraction of what their works normally go for, simply because there’s a nude in the picture.”

He was right, of course. For all our talk about being sexually liberated, the Puritan heritage hangs heavy on American culture. Pornography flourishes in private, but when it comes to nudity in public, a naked lady on a museum wall can set off demands to know why the museum is promoting the display of a young woman who is apparently, as our grandparents would say, No Better Than She Should Be. And if the model is not Playmate of the Month material, the condemnation can be even worse. It seems that if the viewer is going to be shocked, he at least expects to be titillated as well.

I don’t expect this column to change that situation for museums, but I would like to relate a personal experience that came about early in my dealing career. I was working for Ira Spanierman, and he had purchased a painting by Frank Duveneck (1848-1919), which ended up being hung in my office.

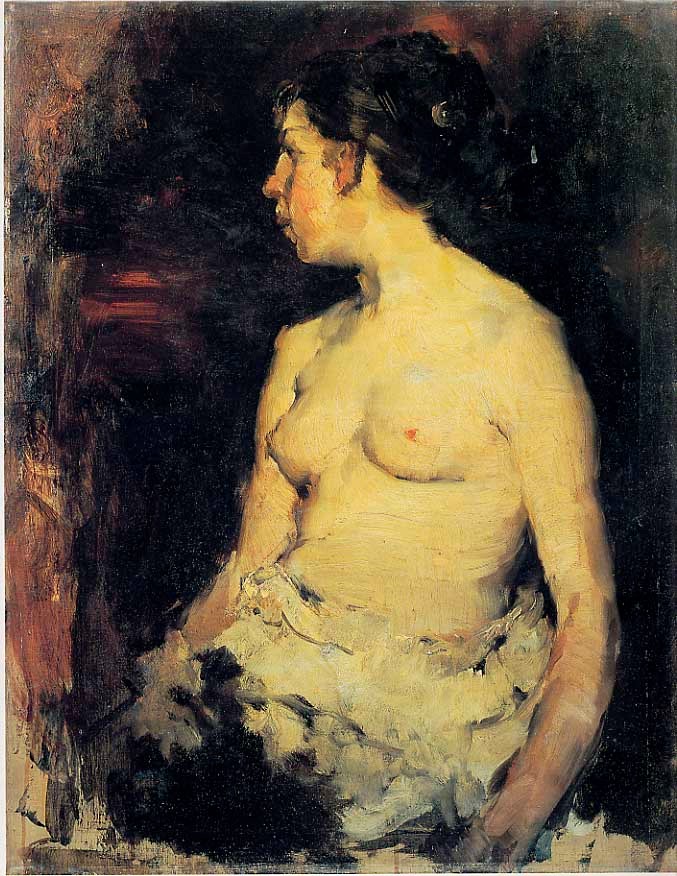

The sitter resembled a rawboned fishwife, and the rendering was what I came to learn was quintessentially Duveneck’s – fat, oily brushstrokes with lots of scumbling. Duveneck loved the 17th century Flemish painters with their dark, rich undertones, and he was usually uninterested in crossing artistic t’s and dotting artistic i’s, at least in the paintings he did for himself. When he got the effect he was after, the painting was finished.

At first, I sneered at what I regarded as a mess – “She looks like a side of beef!” I protested. But as I lived with this painting over a few months, I came to love it. I loved the magic it had, the magic all great art has, when a welter of brushstrokes miraculously coalesces into something representational. I loved how each brushstroke functioned simultaneously as delineator of another object and simply as itself, a smear of chemical substance. The subject of Duveneck’s painting was a woman, but it could just as well have been a side of beef or a vase of roses. The virtuosity of its brushwork was what kept me looking at the painting.

I’ll talk about other “difficult” subject matter in the future. For the moment, I’ll just say to collectors, don’t dismiss nudes out of hand when looking for a painting by a particular artist. You will find your pennies stretching a lot further.

It occurs to me that the nudes I’ve been talking about here are all of women. You want to stretch your pennies even further? Try a male nude. But that’s a subject for another column.