Magazzino Italian Art, a terrific small museum that opened in Cold Spring, NY a few years ago, currently has on view an exhibition of works by Costantino Nivola (1911-1988). Nivola was born in Sardinia, the son of a mason, and attended art school near Milan. He went to work as a designer for Olivetti in Milan, but fled fascist Italy with his Jewish wife in 1938 as war approached. They came to New York and settled in Greenwich Village. Nivola pieced together a living, working as art director for several magazines and doing other design projects.

In 1948 Tino, as he was called, was able to buy a farmhouse in Springs, a village on Long Island near East Hampton which had already been discovered as an inexpensive place to live by several Abstract Expressionist artists, most notably Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. There Tino and Ruth created a home that was really an environment, with house and garden intermingling with each other, and they raised a family. (Nivola’s grandson Alessandro is earning rave reviews these days for his performance in the Sopranos prequel movie, The Many Saints of Newark.)

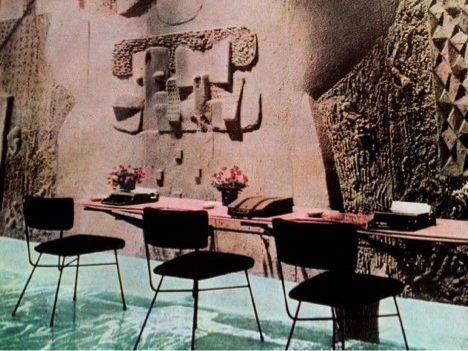

Nivola’s big break came in 1954 when he was commissioned to design the showroom of Olivetti’s flagship store on Fifth Avenue. Olivetti wanted something that would get attention from passersby, and Nivola certainly delivered, with marble floors, modern furniture, and cast stone wall reliefs of his own design. (The reliefs are no longer there. When the showroom closed, they were donated to Yale University, where they are now installed.)

Nivola continued to do public commissions in New York and elsewhere, creating sculptures and installations for schools, housing projects, and government buildings right up to his death in 1988. He was respected as an innovative designer, but his non-architectural work’s reputation suffered by comparison, as if his small sculptures were just a hobby. They came up at auction from time to time after his death, selling in the low-four-figure range when they cracked the thousand-dollar barrier at all.

Things have been changing in the past decade and especially of late. A foot-wide bronze wall relief sold at an auction in Rome for under $5,000 in 2011, but another cast from the same edition sold for over $18,000 in Milan this past April. Still, Nivola was an artist unknown to most collectors in this country. I knew of him because I had appraised a collection of 63 of his works which are owned by a friend of my wife’s and mine who knew and worked with Nivola late in the artist’s life.

At the time of my appraisal, the record for a Nivola work at auction was $7,000, set by a two-foot-wide bronze sculpture offered by a Hudson Valley auction house in 2017. Using the auction records as comparatives, I set the values in my appraisal at modest levels.

My friend called me a couple of weeks ago. “Did you see what just happened at Swann Galleries?” he gasped. Swann, a New York auction house, had a painted sculpture of cast stone by Nivola, just under a foot high, in its September 21 sale. They had put a very modest estimate of $2,000-3,000 on the work. The piece sold for $45,000 including premium.

“What the heck happened?” my friend demanded. Part of the reason for the high price may have been the sculpture’s provenance: it was from the estate of Virginia Zabriskie, a noted New York art dealer. That provenance, however, could not count for everything. Someone went all-out in chasing the sculpture, but there had to be someone else who was almost equally determined to buy the piece. You can’t have a record price without an underbidder.

In the cases of unexpected record prices, cynical dealer types such as myself may suspect a little jiggery-pokery. You’re not generally allowed to bid on your own work at auction, though an exception may be made when the heirs to an estate can’t agree on who should get a particular piece. In that case, putting the work at public auction may be the best solution: all the heirs will get a share of the proceeds from the sale, and if the winning bidder happens to be one of the heirs, the piece was purchased fairly.

But I have also known dealers who have salted away several works by a particular artist in order to place a piece at public auction and have a couple of straw buyers run up the price (I’m not naming names). For the price of the commission paid to the auction house, the dealer now has an auction record to which he can point as he gradually brings the other works onto the market at the new price level.

Did that happen here? Is someone sitting on a stock of Nivola works? I won’t presume to guess. The result of the sale, however, means that Costantino Nivola will be getting a serious look by more collectors. That’s good – his works deserve it.