When Norman Rockwell died in 1978, Time Magazine art critic Robert Hughes briefly discussed the artist’s place in American art. Hughes acknowledged that Rockwell in his last years had moved beyond the soda-fountain-American-flag-and-Mom’s-apple-pie subject matter that had made him a household name over the years in which his illustrations regularly appeared on the covers of The Saturday Evening Post and other publications. Rockwell’s world view had darkened in the 1960’s. His later works had dealt with school desegregation and with the murder of civil rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner.

“But these did not represent the essential Rockwell as far as his public was concerned,” wrote Hughes. “What they wanted was a friendly world, shielded from the calamities of history and the endemic doubts that are the modernist heritage, set down in detail, painted as an honest grocer weighs ham, slice by slice, nothing skimped; and Norman Rockwell gave it to them for 60 years. He never made an impression on the history of art, and never will. But on the history of illustration and mass communication his mark was deep, and will remain indelible.”

So things seemed in 1978, at least to one important critic. But the art world was already changing. The modernist paradigm had proved unsustainable – I mean, after you’ve pared everything down to Minimalism, what else is there to do? – and a move back to figuration was already underway. Pop Art had brought back the figure, albeit in an ironic fashion, with artists such as Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist using images and painting techniques derived directly from what had hitherto been dismissed as “commercial art.” Photorealists used recognizable subject matter. Where did Rockwell fit into all this?

I’ve been musing about this ever since Roberta and I visited the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, a couple of weeks ago. No matter what art criticism has said about Rockwell, the people have spoken. He is an indelible part of contemporary culture. How many other museums devoted to the work of a single artist draw hundreds of thousands of visitors each year? The only one that readily comes to mind is the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg. Salvador Dali, about whom I have written elsewhere, is another artist whose work is seemingly impervious to negative criticism.

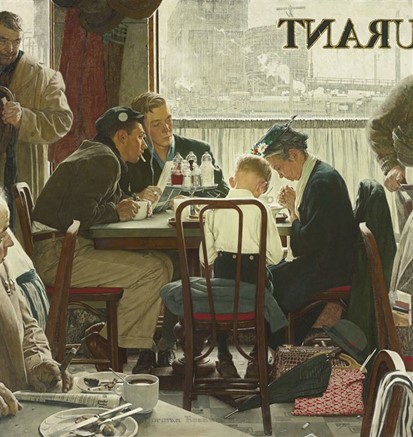

Whatever art critics have said, the art market takes Rockwell extremely seriously. 71 of his works have sold at auction for over $1,000,000, with the record being held by “Saying Grace,” which sold for $46,084,000 eleven years ago.

Norman Rockwell, “Saying Grace,” 1951. Oil on canvas, 43 x 41 inches.

Photo courtesy Sotheby’s

The painting is a marvel of technique with its X-shaped composition and its precisely rendered detail. Any painter would be happy to have such chops.

A painter with an entirely different style, Willem de Kooning, was a great admirer of Rockwell’s paintings. The critic Peter Schjeldahl confirmed this. I took instruction . . .from de Kooning, who opened a book to a reproduction, handed me a magnifying glass, and made me peruse Rockwell’s minuscule but almost fiercely animated painterly touch. “See?” said de Kooning. “Abstract Expressionism!”

There’s also a report of de Kooning looking at Rockwell’s painting “The Connoisseur,” which shows a very proper gentleman standing in front of Rockwell’s imitation of a Pollock drip painting, and exclaiming, “Square inch by square inch, it’s better than Jackson!”

Out-Pollocking Pollock? Perhaps de Kooning was pulling someone’s leg, but the fact remains that Rockwell was a master. The success of his paintings in the art market has increased the number of works being offered by lesser-known illustrators. Works by other Saturday Evening Post cover illustrators such John Falter and John Atherton have brought five- and six-figure prices in recent years. But I suspect that Rockwell will always be in a class by himself. His loving caress of minutia sets him apart. “He went beyond the requirements,” said author and critic John Updike. “He could have painted with less loving detail. He could have had fewer little anecdotal touches and facial expressions in his work. But he went always to fill the glass to the brim”

In the end Rockwell achieved something that few artists do: he created images that have escaped the paintings they were in to become anonymous memes in the area of social media. Many people may not know the names of Grant Wood or Edvard Munch, but they are familiar with “American Gothic” and “The Scream” through countless appropriations and parodies. Those paintings have broken free from their art historical context to become part of the general culture.

Rockwell’s “Rosie the Riveter,” painted in 1942, was an icon of the feminist movement long before it sold for $4,959,500 twenty-two years ago. Within a day of Joe Biden’s announcement that he would not run for re-election, an image by Theoplis Smith III (a.k.a Phresh Laundry) that has a direct connection to Rockwell’s painting was all over the internet.

Norman Rockwell, “Rosie the Riveter,” 1942.

Oil on canvas, 52 x 40 inches.

Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

Theoplis Smith III, “Rosie Backbone,” 2021.

Archival pigment print, 20 x 16 inches

Photo courtesy Phresh Laundry.

How many of the young people circulating this meme are aware of its connection to Rockwell? I don’t know, but such lack of knowledge doesn’t matter, as it only proves my point that many of Rockwell’s creations have passed into general culture. In my view, that’s a sign of a major artist.